Dear Commons Community,

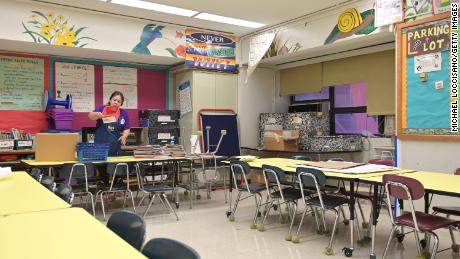

The New York City public schools see themselves in a predicament of rethinking their strategy for dealing with the coronavirus. Over the next two weeks, over one million parents in New York City must make a wrenching decision: Should they send their children into classrooms this school year or keep them learning from home, likely until at least next fall?

Last week, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that parents would have until Nov. 15 to decide whether to enroll their children in hybrid learning, a mixture of in-person and remote instruction, for the remainder of the school year.

The city had originally promised parents they could opt into the hybrid program every few months. But the mayor changed the rules because about only a quarter of the district’s 1.1 million students have shown up for in-person classes since September, far fewer than predicted. That has made it difficult for the city to know how to allocate teachers, the mayor said.

Now, the many parents who have kept their children home, whether for safety, convenience or consistency, need to decide: Is hybrid learning working?

It is a question parents in many other places across the country and world are also facing, as more districts prepare to open for at least some mixture of in-person and remote classes. But the choice is particularly fraught in New York City, once a global epicenter of the virus and now one of the few large urban districts in the United States to offer any classroom instruction. As reported by The New York Times. (My colleague, David Bloomfield, is cited in the article.)

“Intuitively, parents understand that the best place for kids is in school,” said Eric Goldberg, an elected parent leader in Manhattan who has chosen hybrid for his own children. “But what is it about the New York City public school experience that is leading families to choose remote learning? When the in-school experience is so compromised and inferior, people think, ‘Why am I doing this?’”

Mr. Goldberg and other parents lamented that the city’s reopening plan focused almost exclusively on reconfiguring school buildings to open safely — which they agreed was the most important goal — but gave little thought to how children were actually going to learn.

As a result, although the city has seen very low virus transmission in its schools so far, many parents and educators have begun to raise urgent concerns about the quality of the hybrid program. In particular, they have questioned a slew of restrictions agreed to by City Hall and the teachers’ union, the United Federation of Teachers, over the summer that limited when and how educators can teach, and that created a major staffing shortage that is not entirely resolved.

That deal, which the city accepted as part of a frenzied effort to reopen schools, held that teachers could not be required to conduct both in-person and remote lessons on the same day — forcing the city to hire thousands of teachers to make up the difference.

The agreement was “probably the biggest screw up” in the city’s halting effort to reopen, said David Bloomfield, a professor of education at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center and Brooklyn College.

The same deal discouraged teachers from livestreaming their lessons in school buildings to children learning at home over concerns that it would strain teachers and be ineffective for students. But the practice is being used by some local private schools, as well as in many schools across the country.

In an interview, Michael Mulgrew, president of the United Federation of Teachers, brushed off questions about whether he would consider renegotiating that deal. Instead, he acknowledged that there were major problems with hybrid instruction, but blamed the city for not anticipating the staffing crunch and not developing a better instructional plan.

“They will say, ‘Oh, it’s the U.F.T.’s deal,’” Mr. Mulgrew said about the city. “They should be saying, ‘We’re incompetent, and we shouldn’t be in charge of this anymore.’”

Danielle Filson, a spokeswoman for the city’s Department of Education, defended the reopening effort, pointing out the difficulty of hiring so many new teachers in a short time.

“Nothing replaces an in-person education for our kids,” she said in a statement. “That’s why we moved heaven and earth to reopen buildings this fall, adding thousands of teachers, an unprecedented testing regime, resources for health and safety, and 350,000 internet-enabled iPads to ensure continuity in instruction.”

The city has spent about $50 million on 5,600 new full-time teachers and substitutes, and has moved an additional 2,000 department staff members with teaching licenses into schools. That is a significant sum for a city that is facing a catastrophic fiscal crisis caused by the pandemic. Last month, the city said it could not afford $900 million in back pay owed to teachers this year under their contract.

Paula White, the director of Educators for Excellence-New York, a teachers’ group that represents thousands of city educators, said the staffing deal was “a watershed moment. Its impact will be felt for some time.”

“Every new teacher represents a significant investment,” she added. “At a time when budgets are strapped more than ever before, every cost has to be weighed against the opportunity cost for other investments.”

But the city still needs to hire several thousand more educators to make hybrid learning work according to plan. As a result, the city abandoned a promise that children enrolled in the hybrid program would receive live teaching on the days they were at home.

The shortage has also meant that many high schools can open their doors only to students taking online classes, because principals did not have enough teachers to staff elective and high-level courses both remotely and in person.

Further complicating the scheduling jigsaw puzzle is that about 24 percent of city teachers have been granted medical accommodations to work from home through December.

Educators across the city say they have found it impossible to abide by the staffing agreement. So, they have created workarounds.

Verneda Johnson, a science teacher in Harlem, said her middle school’s principal and teachers decided to skirt the agreement by establishing that teachers should be able to hold in-person and remote classes on the same day.

“We thought, let’s make the schedule as needed, and if someone ends up with something they find untenable, we’ll fix that,” Ms. Johnson said. “But at the end of the day, you have to do what’s the best for school.”

The president of the city’s principals’ union, Mark Cannizzaro, said educators had “really, really tried to make lemonade out of lemons.” But, he added, “Long-term, I don’t think this is going to be sustainable.”

Jonathan Kingston, whose two sons are enrolled in the hybrid program at Public School 128 in Middle Village, Queens, is furious at the city and the teachers’ union for discouraging the livestreaming of lessons.

P.S. 128 has a staffing shortage, and livestreaming appears to be the only way for students in person and online to learn the same material at roughly the same pace. With little guidance from the city, the school was only able to set up livestreaming starting just two weeks ago.

The city “could have done this in July, August, even September, instead of throwing our teachers and principal into an unwinnable situation,” Mr. Kingston said.

Still, despite the logistical morass, Mr. Kingston and other parents said they would stay in the hybrid program, mostly because their children were so delighted to be back in the classroom.

“So far, we are very happy,” Elga Castro, whose daughter is a third grader at Dos Puentes Elementary School in Washington Heights. “Everything moves to the second place when compared to their happiness about going back to school.”

For all the problems with the hybrid program, educators and parents said remote learning was also far from ideal, though it had improved since the spring.

Some schools are reporting very large remote class sizes, another negative effect of the staffing crunch. Many schools also have not received enough laptops and tablets, and scores of students living in homeless shelters are struggling to log on for their online classes.

Despite such limitations, nearly half the district’s Black and Latino families decided to start the school year remote-only, along with over 60 percent of Asian-American families. White families have opted for remote learning at the lowest rate.

That racial dynamic could undermine the mayor’s assertion that he had a moral imperative to reopen schools for the least advantaged families.

If in the coming weeks only a small percentage of students restart in-person classes, the city has indicated it may increase the number of days that hybrid students can physically attend school, because some classrooms are only about half full.

But if students of color continue to stay away from school in large numbers, the many benefits of in-person schooling — from live instruction to mental health services to hot meals — may not reach many of the most vulnerable students.

That is more evidence that the reopening plan was not built around the needs of children who require more in-person classes, said Mark Treyger, chair of the City Council’s education committee.

Mr. Treyger has recommended that the city essentially start over and offer classroom instruction only to pre-K and elementary school students, children with disabilities and students living in homeless shelters.

“This model is not working,” he said. “I think the time for change was yesterday.”

YES!

Tony