Dear Commons Community,

It is with great pride that I congratulate, Lee Gabay, for being a New York Times’ New Yorker of the Year. Lee graduated our PhD Program in Urban Education in 2013. His dissertation completed under the guidance of David Brotherton was entitled, I hope I don’t see you tomorrow: A Phenomenological Ethnography of the Passages Academy School Program.

Lee was a special student who cared deeply about a lot of things but especially his students at Passages Academy, a NYC public school that provides education, social, and emotional services to students in juvenile detention. I had conversations with him about his young charges and it was cleared he was completely devoted to them and most sensitive to their difficult life situations.

I also have had the pleasure of attending Knick and Yankee games with Lee, his father and his wife Chrystal. He has also been blessed with a beautiful daughter, China Grace.

Below is the New York Times piece on Lee’s award.

Congratulations again, Lee!

Tony

===============================

Lee Gabay, an Inspiring New Yorker!

New York Times, December 27, 2016

===============================

“Before we go on, I want to congratulate you on finishing a book,” Lee Gabay told his students.

“That’s a beautiful thing you did today.”

Mr. Gabay, an English teacher at Brooklyn Democracy Academy in the Brownsville section of the borough, was finishing a lecture on John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men.”

Also required reading in his class: “Holler if You Hear Me: Searching for Tupac Shakur,” by Michael Eric Dyson, about the history of hip-hop and race relations in the United States.

As far as teachers go, Mr. Gabay, 47, who has a Ph.D. in urban education, is somewhat unconventional.

“I loved to learn, but I hated school, always,” Mr. Gabay said, describing himself as having been a class clown. “I think that has inspired what I’ve become, what I wanted to do and the kind of classroom I wanted to create.”

He rides a motorcycle to school. He is fascinated with sneaker culture. He is a vocal Knicks fan.

He sits with students during lunchtime to talk about music. And he winces at the thought of being called Dr. Gabay. Some students simply call him “G.”

A majority of his career has been spent in unconventional settings, teaching literature to students who had been locked up.

While an undergraduate at the University of Southern California, he worked at a group home for children who had been incarcerated. He went on to receive a master’s degree in education from New York University and his doctorate from the City University of New York, where he focused on juvenile offenders.

This led him to teach for more than a decade at Passages Academy, a juvenile detention school in the city, and at his current post at Brooklyn Democracy Academy, a transfer school for under-credited students whose education had been interrupted.

During his four years at the academy, Mr. Gabay has broadened his role to become like an older brother to these struggling teenagers — many of whom have spent time in foster care or in jail. He is as adamant about nurturing them socially and emotionally as he is about preparing them to take tests.

His motto: “Students need to know how much you care before they care how much you know.”

“Brownsville has the worst schools in the city, the worst health care, the most homicides, the worst food — there are no Starbucks here — and I want to give them access to all the good things that I was blessed to have,” said Mr. Gabay, who was born on the Lower East Side and grew up in Great Neck on Long Island.

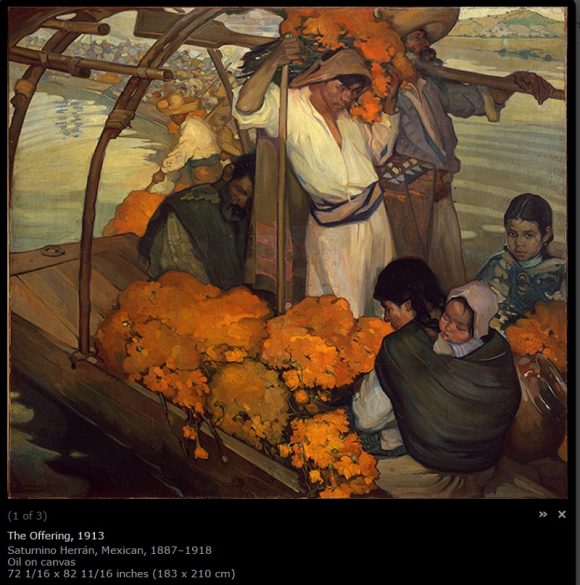

Mr. Gabay at the school: “Students need to know how much you care before they care how much you know.”

He networks relentlessly to open doors for his students.

He brought in a spoken-word performer who inspired one young man to travel to Africa with the artist to study. After Mr. Gabay invited an Oscar-nominee, Jesse Eisenberg, to the school, the actor mentored a student who was passionate about the entertainment industry. When John Wallace, the former Knicks player, came to class, another student ended up with a job.

“People at school are like, ‘Gabay, how do you do that?’ And I’m like, ‘It’s simple. Just reach out and say thank you,’ ” he said. “It’s not a strategic thing; I think it comes from someone’s heart.”

It is not quite the same as the work done by large nonprofits; Mr. Gabay says he is much more informal, focusing on the little things — small deeds that can inspire one person, and have the potential to turn a life around.

“When you go places, you’re always thinking: ‘What can benefit the students? What can benefit the school?’ ” he said.

“You don’t have an off switch when you teach.”