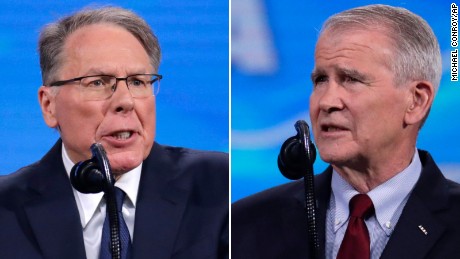

Ronald Lauder, president of the World Jewish Congress, and Richard Parsons, former Time Warner chief executive and Citigroup chairman who sits on the board of Estée Lauder Companies.

Dear Commons Community,

The debate over the admissions test for New York City’s specialized high schools such as Stuyvesant and the Bronx High School of Science was ratcheted up this week when Ronald Lauder announced that he was financing a multimillion-dollar lobbying, public relations and advertising effort called the Education Equity Campaign, whose immediate goal was to ensure that Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to eliminate the entrance exam does not pass the New York State Legislature. Mr. Lauder, who is the president of the World Jewish Congress, is being joined by Richard Parsons, the former Time Warner chief executive and Citigroup chairman who sits on the board of Estée Lauder Companies, in this effort. Essentially Lauder and Parsons want to keep the existing test for New York City’s elite schools, and propose other ways to increase the number of black and Hispanic students. The diversity issue flared last month when the city disclosed that only seven black students received offers to Stuyvesant out of 895 spots.

Though black and Hispanic students make up nearly 70 percent of New York’s public school students, they represent only 10 percent of the elite schools’ population. Asian-American students, who make up 15 percent of the system as a whole, hold about two-thirds of those schools’ seats. Many come from low-income and immigrant families.

The admissions test, which tens of thousands of eighth graders take every year, has become a focus of the debate, with opponents calling it discriminatory.

Below is an excerpt from an article covering this story that appeared in today’s New York Times:

“Ronald S. Lauder, the billionaire cosmetics heir, and Richard D. Parsons, the former chairman of Citigroup, have for decades had their hands in New York City affairs. Mr. Lauder ran a failed bid for mayor and successfully led a campaign for term limits for local elected officials. Mr. Parsons has been a prominent adviser to two mayors.

Now, they are teaming up to try to influence one of the city’s most intractable and divisive debates: how to address the lack of black and Hispanic students at Stuyvesant High School, Bronx High School of Science and the other elite public high schools that use a test to determine admission.

Mr. Lauder this week announced that he was financing a multimillion-dollar lobbying, public relations and advertising effort called the Education Equity Campaign, whose immediate goal is to ensure that Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to eliminate the entrance exam does not pass the State Legislature, people involved in the effort said.

More broadly, the two men are trying to make their mark on the future of the system, the nation’s largest, with 1.1 million students.

Their effort amounts to a new challenge to Mr. de Blasio’s education agenda from people whose ideas are more reminiscent of former Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg’s vision. They are seeking to forge connections to leaders in Albany who are skeptical of the mayor’s philosophy.

They are championing a range of educational ideas that include more gifted and talented programs, more test preparation, better middle schools and more elite high schools. Mr. de Blasio’s administration, on the other hand, is skeptical of high-stakes testing and academic tracking in the school system.

Mr. de Blasio is seeking to replace the test for the eight so-called specialized schools with an approach where top performers from each middle school would be offered spots.

Mr. Lauder and Mr. Parsons — who is making a sizable donation to the effort — have hired several lobbyists and political strategists to sway opinion in Albany and, ultimately, to achieve a broader aim of overhauling a long-struggling school system. They include a protégé of the Rev. Al Sharpton and a firm with ties to Mr. Bloomberg.

In a fight that is already reaching a boiling point, “the fact that it’s very rich people who are at the helm of it makes it distinctive,” said Aaron Pallas, a professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

Mr. Lauder is not merely a deep-pocketed outsider wading into a fraught local issue. Heir to the Estée Lauder fortune, he graduated in 1961 from Bronx Science. He is a relative rarity: Not many wealthy students have historically attended the elite schools, which have long been seen as an engine that propels low-income children to the middle-class.

Mr. Lauder and Mr. Parsons declined to be interviewed but released statements explaining their support for the Education Equity Campaign.

“The education I received at Bronx Sci shaped the person I am today,” Mr. Lauder said. “I want more New Yorkers, from every borough, to have access to a world-class public education.”

Mr. Parsons, who is considered one of the nation’s foremost black business leaders, attended a public high school in Queens, but not a specialized school.

“Greater diversity in our schools is an imperative, but the battle cannot be won simply by lowering standards,” Mr. Parsons said. “I’m backing this effort because I believe we must do the hard work of improving our public education system so that all children have the opportunity to realize their full academic potential.”

Mr. de Blasio lashed out at the spending by Mr. Lauder and Mr. Parsons, portraying it as a misguided attempt by wealthy donors to meddle in public schools.

“The billionaire class is going all out to keep the status quo, and deprive black and Hispanic kids of their shot at the city’s specialized high schools,” he said. “It’s a disgusting misuse of money and power, and we’re going to fight it.”

The diversity issue flared last month when the city disclosed that only seven black students received offers to Stuyvesant out of 895 spots.

Though black and Hispanic students make up nearly 70 percent of New York’s public school students, they represent only 10 percent of the elite schools’ population. Asian-American students, who make up 15 percent of the system as a whole, hold about two-thirds of those schools’ seats. Many come from low-income and immigrant families.

The admissions test, which tens of thousands of eighth graders take every year, has become a focus of the debate, with opponents calling it discriminatory.

As a result, proponents of the current system are facing pressure to find ways of diversifying the schools while keeping the test. Projections show that under Mr. de Blasio’s plan, the schools would enroll many more black and Hispanic students, but Asian-Americans would lose about half their seats.

The equity campaign’s ideas in some ways recall education policies embraced by Mr. Bloomberg, whose sweeping education agenda has been largely eliminated by Mr. de Blasio.

Tusk Strategies, a political strategy firm with close ties to Mr. Bloomberg, said it was orchestrating the effort for a fee of between $50,000 and $150,000 a month.

Also on the payroll are Albany lobbying firms, including Patrick B. Jenkins & Associates and Bolton St.-Johns, known for their connections to Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo’s administration and the State Legislature, respectively.

The group’s board of advisers, who are also being compensated, includes education experts who have supported Mr. Bloomberg’s accountability-driven brand of education reform.

The public face of the campaign, the Rev. Kirsten John Foy, whose civil rights organization is receiving a contribution for its involvement, is a prominent minister and a Sharpton ally. The campaign is planning to spend at least $1 million on advertisements alone. Neither the website nor the ads bear any mention of Mr. Lauder or Mr. Parsons.

Mr. Foy said the low black and Hispanic enrollment in the specialized schools should be a wake-up call about problems in the city’s 1,800 schools. He dismissed Mr. de Blasio’s plan, saying, “Do not miss this opportunity by taking the path of least resistance.”

The group is hoping that Albany lawmakers adopt their platform, elements of which Mr. Bloomberg embraced as ways to make an impact on the specialized schools and to advance a grander theory of change.

The equity campaign’s least-defined component is a call to lift the quality of hundreds of city middle schools.

Mr. de Blasio’s $773 million school improvement plan, Renewal, was canceled after it failed to achieve its promised results. Mr. Bloomberg’s initiative to create more small schools showed positive outcomes.

The group’s paid board of advisers includes Michael Lach, an academic at the University of Chicago who previously worked for Teach for America and for former education secretary Arne Duncan. (Mr. Parsons sits on Teach for America’s board.)

“I want to be a part of something that’s advocating for the long slog, unsexy work of slowly making schools better,” Mr. Lach said.

But some education experts noted that the equity campaign’s suggestions, including additional specialized high schools, expanded test prep and an option for students to take the exam in school, rather than on the weekend, have been tried before in pilot form with largely disappointing results. And they argue that expanded free prep will simply encourage more private prep.

Though Mr. Bloomberg added five new specialized schools, they too have generally enrolled shrinking numbers of black and Hispanic students.

Mr. Foy said previous attempts had been insufficient. “If you look at the scale of our system, the sheer numbers, those pilots have not been adequate.”

Still, critics have questioned why the billionaire and the businessman’s focus on improving city schools is based on maintaining the test.

Richard Buery, the head of policy at the charter school network KIPP and a black Stuyvesant alumnus, said he found it odd that benefactors “would look at the state of education in New York City and decide that keeping the specialized high school exam is where their education philanthropy should go.”

This is an important development in terms of the politics of public schooling in New York City. While the initial focus may be on admissions to specialized high schools, it will carry over into other controversial issues related to charter schools, standardized testing and other accountability measures.

Tony

Donald Trump and Lachlan Murdoch

Donald Trump and Lachlan Murdoch