Dear Commons Community,

I have just finished reading Rinker Buck’s Life on the Mississippi: An Epic American Adventure, which tells the story of his adventure in sailing down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in an 1800s-style wooden flatboat. This book follows the same pattern as Buck’s bestseller, The Oregon Trail.

Life on the Mississippi… opens with the important history that flatboats played in the expansion of the country in the 1800s from the East to the West and South. These wooden boats carried settlers and their belongings as well as commercial goods from the East to towns along these two rivers and for many, eventually reaching New Orleans. Buck builds a flatboat replica named Patience for his journey and brings on a small crew of enthusiasts for his trip. For readers who are boat owners, Buck’s narratives of the intricacies of navigating the waters of the two great rivers during his two-thousand mile trip are interesting. However, the most significant passages of this book are when he describes the historical importance of the rivers for the rise (and for some fall) of major towns and cities such as New Madrid and Natchez, the slave trade in the Southern states, and the displacement of the Cherokee, Choctaw and other indigenous tribes due to the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

In sum, I found Life on the Mississippi… a good read and a fine contribution to my understanding of the part these two rivers played in the development of our country.

Below is a review that appeared in the New York Times Book Review.

Tony

—————————–

The New York Times Review of Books

From Pittsburgh to New Orleans, on a 19th-Century-Style Flatboat

In “Life on the Mississippi,” Rinker Buck takes a lengthy river trip to examine a uniquely American history.

By Ben McGrath

Published Aug. 9, 2022

LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI: An Epic American Adventure, by Rinker Buck

A dry cleaner in Yankton, S.D., once told me that he had spied so many fussily costumed boaters from the banks of the nearby Missouri River that he’d grown weary of new arrivals. “People are recreating Lewis and Clark,” he said. “It happens here all the time.” He loved the river, for its waterfowl and promise of imaginative escape, but not always its thru-traveling flock, who, if not reprising the migration of previous generations, often seemed to be proselytizing for one thing or another: energy independence, say, or sobriety. “Some of these people are a little on their high horse, you know?” he said. To meet a waterborne voyager whose only cause was wanderlust: That was novel.

I thought of my conversation with the dry cleaner while reading Rinker Buck’s engaging “Life on the Mississippi: An Epic American Adventure,” which recounts the author’s 2,000-mile journey from Pittsburgh to New Orleans aboard a purpose-built wooden flatboat, like the ones used by Appalachian farmers in the decades after the Revolutionary War. His rotating crew includes a sometime Meriwether Lewis impersonator whom Buck loathes, not only for his casual racism and misogyny but for his pretension — archaic speech, suitcase bulging with 19th-century outfits.

Historical re-enactors, Buck writes, are “overdressed losers.” Readers of his previous book, “The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey,” will recognize the particular sensitivity. For that entertaining project, Buck traversed the old pioneer route by covered wagon, while railing against those purists who would lament the intrusions of asphalt and soft serve. The frontier was ever debased. Still, you might say that Buck is a re-enactor by another name: a travel writer, who delights in incongruity and in history’s rhymes.

He also comes by his wanderlust organically. When he was 7, in 1958, Buck accompanied his parents and siblings on a wagon ride through New Jersey and Pennsylvania to “see America slowly,” as his father, a magazine publisher, put it. When he was 15, and more inclined toward speed, he joined an older brother in the cockpit of a Piper Cub and leapfrogged the continent. “We had only a shopping bag full of maps, no radio and a compass that barely worked,” he writes. “Follow the highways, son,” his father would say, “or pick out a river.”

The rivers at the heart of this book are not just the oft-chronicled one in the title (borrowed, of course, from Mark Twain) but also the Ohio, which set a young country in westward motion and thereby defined Americans “as a migratory people,” Buck writes, “radically departed from our European antecedents.” Some followed the water’s gravitational pull only to sell their wares, and the timber on which they drifted, and hoof back. Others resettled downstream. At the time of the country’s birth, about 3 percent of the non-Native population resided west of the Appalachian range. By 1830, that figure had floated to 30 percent. “At the edge of civilization in North America, at the wharves and bursting river towns of the new territories, social caste and standing belonged to the uprooted, the wayfarers, the self-made men and boys struggling with their oars to land a broadhorn against the current.”

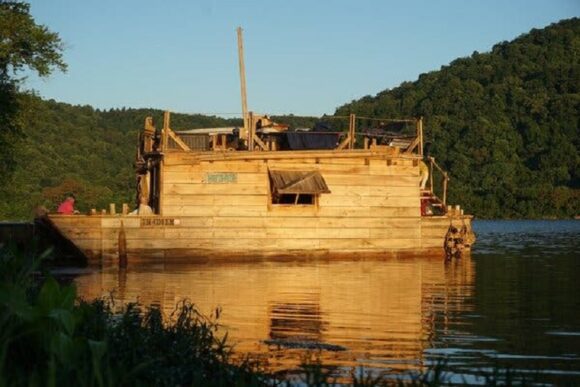

Broadhorn was another name for a flatboat — square of bow, shallow of draft and requiring little in the way of construction expertise — because the long, curved steering oars were wielded from atop the cabin and appeared like giant horns at a squint. Buck names his flatboat Patience — and opts, pragmatically, for an inboard motor, which he pilots from the roof deck, like his predecessors. His heightened perch is the perfect vantage both for admiring the landscape of conservation forest punctuated by Rust Belt blight, and for contemplating the economic winds that have lately roiled our politics. The decline of the steel industry, he observes, stirred a different type of growth, with sprigs of aspen and birch extruding from West Virginian smokestacks and window transoms. “The persistence of man was dramatically yielding to the persistence of nature,” Buck writes.

Coal was another matter: too recently decimated, by offshore drilling and fracking, for nature’s reclamation to inspire awe. Many marinas, meanwhile, were abandoned, casualties of the 2008 recession and subsequent flooding. The loss of so much disposable income meant fewer fishermen and water skiers, which in turn led to a reduction of refueling stations. A savvy crew member of the Patience charms a struggling business owner into donating several crucial backup gas tanks to the mission by slagging the federal government. Surveying the lonely river valley, Buck has the realization that the same ridgelines that lent feelings of containment and serenity to a boat captain effectively shielded the extent of deindustrialization from the still-bustling interstates on the far sides. Geography is destiny. No wonder the populist groundswell of 2016 caught so many landlubbers by surprise.

“You’re going to die,” everyone warns Buck, both before and throughout an adventure in which he never comes close. I hesitate to identify this as a disappointment, though I suspect the author would sympathize with this reader’s yearning for vicarious adversity to match his riparian surroundings. If Buck is a proselytizer for any cause while afloat, it may be for the perverse pleasure associated with cracking one’s ribs, which he does — memorably, and for the fifth time — while balancing a tray of biscuits and gravy, eggs and bacon (“real food, trucker chow”) for his crew and ascending a poplar staircase to the deck amid oncoming rollers from a tug. The breakfast survives his fall intact; the rib cage does not. “I like what being a champion rib-breaker says about my life,” he writes. “Rib breaks and their pain are a reminder of my foolhardiness, perhaps, or my addiction to adventure, or my need for comeuppance for having led such a fortunate, happy life.”