One-fifth of computer science papers may include AI-written sentences.

W. LIANG ET AL., NAT HUM BEHAV (2025) BEHAV (2025) HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1038/S41562-025-02273-8

Dear Commons Community,

A massive, cross-disciplinary look at how often scientists turn to artificial intelligence (AI) to write their manuscripts has found steady increases since OpenAI’s text-generating chatbot ChatGPT burst onto the scene. In some fields, the use of such generative AI has become almost routine, with up to 22% of computer science papers showing signs of input from the large language models (LLMs) that underlie the computer programs.

The study, which appeared last week in Nature Human Behaviour, analyzed more than 1 million scientific papers and preprints published between 2020 and 2024, primarily looking at abstracts and introductions for shifts in the frequency of telltale words that appear more often in AI-generated text. “It’s really impressive stuff,” says Alex Glynn, a research literacy and communications instructor at the University of Louisville. The discovery that LLM-modified content is more prevalent in areas such as computer science could help guide efforts to detect and regulate the use of these tools, adds Glynn, who was not involved in the work. “Maybe this is a conversation that needs to be primarily focused on particular disciplines.”

When ChatGPT was first released in November 2022, many academic journals—hoping to avoid a flood of papers written in whole or part by computer programs—scrambled to create policies limiting the use of generative AI. Soon, however, researchers and online sleuths began to identify numerous scientific manuscripts that showed blatant signs of being written with the help of LLMs, including anomalous phrases such as “regenerate response” or “my knowledge cutoff.”

“On the surface, it’s quite amusing,” says Glynn, who compiles Academ-AI, a database that documents suspected instances of AI use in scientific papers. “But the implications of it are quite troubling.” LLMs are notorious for “hallucinating” false or misleading information, Glynn explains, and when obviously AI-generated papers are published despite rounds of peer review and editing, it raises concerns about journals’ quality control.

Unfortunately, it has gotten harder to spot AI’s handiwork as the technology has advanced and authors who use it have become more proficient at covering their tracks. In response, scientists have looked for subtler signs of LLM use. For the new study, James Zou, a computational biologist at Stanford University, and colleagues took paragraphs from papers written before ChatGPT was developed and used an LLM to summarize them. The team then prompted the LLM to generate a full paragraph based on that outline and used both texts to train a statistical model of word frequency. It learned to pick up on likely signs of AI-written material based on a higher frequency of words such as “pivotal,” “intricate,” or “showcase,” which are normally rare in scientific writing.

The researchers applied the model to the abstracts and introductions of 1,121,912 preprints and journalpublished papers from January 2020 to September 2024 on the preprint servers arXiv and bioRxiv and in 15 Nature portfolio journals. The analysis revealed a sharp uptick in LLM-modified content just months after the release of ChatGPT. That this trend appeared so soon “means that people were very quickly using it right from the start,” Zou says.

Rise of AI

The amount of artificial intelligence (AI)-generated text in scientific papers had surged by September 2024, almost 2 years after the release of ChatGPT, according to an analysis.

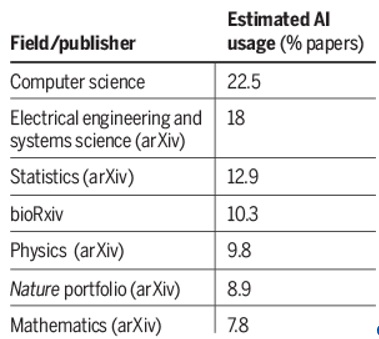

Certain disciplines exhibited faster growth than others, which may reflect differing levels of familiarity with AI technology (see table, below). “We see the biggest increases in the areas that are actually closest to AI,” Zou explains.

By September 2024, 22.5% of computer science abstracts showed evidence of LLM modification, with electrical systems and engineering sciences coming in a close second—compared with just 7.7% of math abstracts. Percentages were also comparatively smaller for disciplines such as biomedical science and physics, but Zou notes that LLM usage is increasing across all domains: “The large language model is really becoming, for good or for bad, an integral part of the scientific process itself.”

University of Tübingen data scientist Dmitry Kobak, whose recent similar study in Science Advances revealed that about one in seven biomedical research abstracts published in 2024 was probably written with the help of AI, is impressed by the new work. “This is very solid statistical modeling,” Kobak says.

He adds that the true frequency of AI use in scientific publishing could be even higher, because authors may have started to scrub “red flag” words from manuscripts to avoid detection. The word “delve,” for example, started to appear much more frequently after the launch of ChatGPT, only to dwindle once recognized as a hallmark of AI-generated text.

Although the new study primarily looked at abstracts and introductions, Kobak worries authors will increasingly rely on AI to write sections of scientific papers that reference related works. That could eventually cause these sections to become more similar to one another and create a “vicious cycle” in the future, in which new LLMs are trained on content generated by other LLMs.

Zou and his colleagues are currently planning a conference where the writers and reviewers are all AI agents, which they hope will demonstrate whether and how these technologies can independently generate new hypotheses, techniques, and insights. “I expect that there will be some quite interesting findings,” he says. “I also expect that there will be a lot of interesting mistakes.”

Tony