Dear Commons Community,

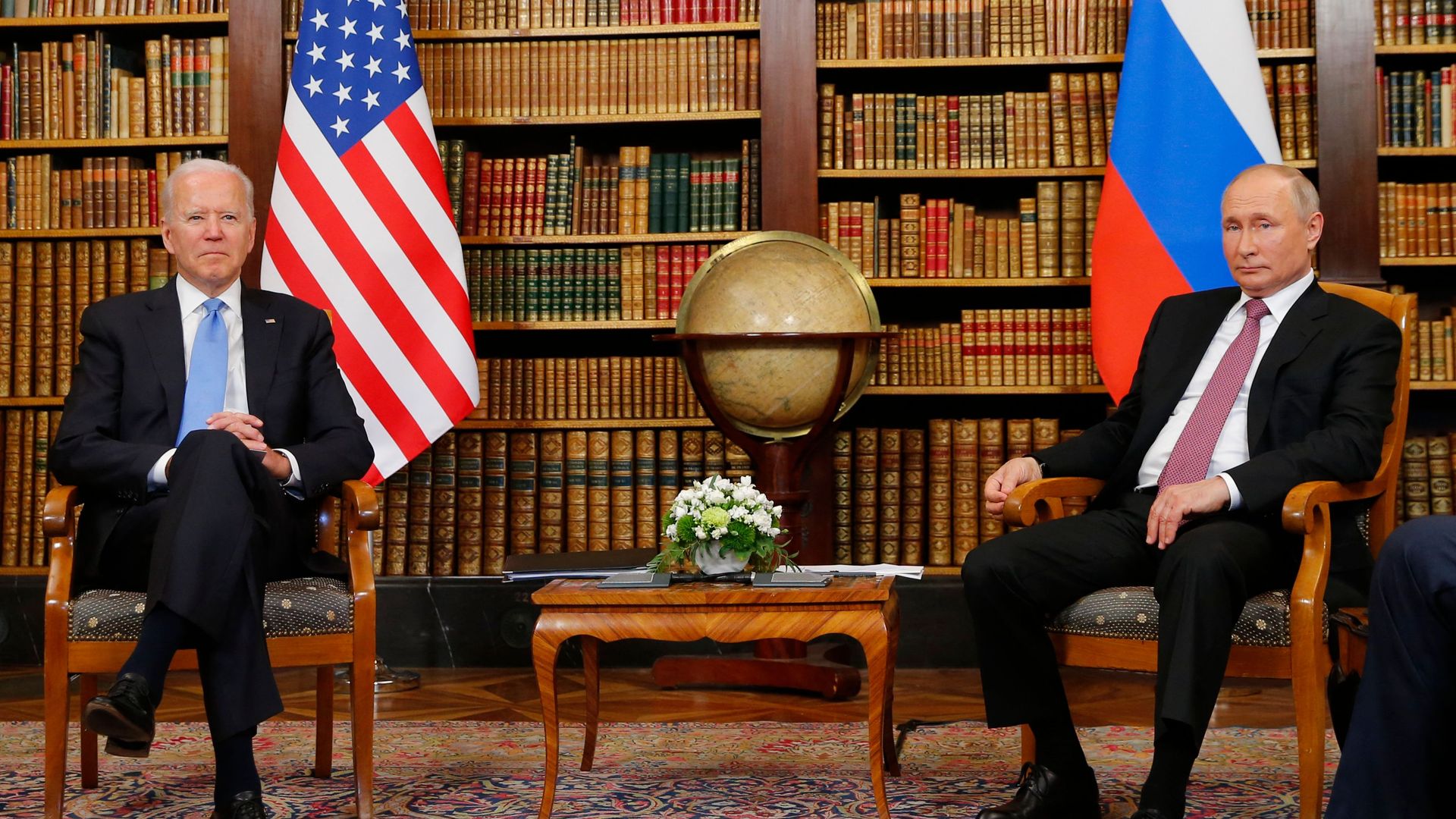

The long-awaited meeting between Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin came and went yesterday with little substantive agreement. Their relationship seems destined to be strained and frustrating, one where the two leaders may maintain a veneer of civil discourse even as they joust on the international stage. New York Times correspondent, Peter Baker, analyzes their meeting in a featured article this morning. Mr. Baker’s main point is that the meeting “was not warm, but neither was it hot.” I watched parts of the post-meeting press conferences held by the two world leaders and I think Baker has it right. Below is an excerpt from his article.

Tony

————————————————————————————————————————-

“As he became the fifth American president to sit down with the troublesome Mr. Putin, Mr. Biden on Wednesday made an effort to forge a working relationship shorn of the ingratiating flattery of his immediate predecessor yet without the belligerent language that he himself has employed about the Russian leader in the past.

If their opening encounter in Geneva proves any indication, theirs seems likely to be a strained and frustrating association, one where the two leaders may maintain a veneer of civil discourse even as they joust on the international stage and in the shadows of cyberspace. The two emerged from about three hours of meetings having reviewed a laundry list of disputes without a hint of resolution to any of them and no sign of a personal bond that could bridge the gulf that has opened between their two nations.

Their assessments of each other were dutiful but restrained. Mr. Putin called Mr. Biden “a very balanced, professional man” and “very experienced” politician. “It seems to me that we did speak the same language,” Mr. Putin said. “It certainly doesn’t imply that we looked into each other’s eyes and found a soul or swore eternal friendship.”

As for Mr. Biden, he did not answer when asked if he had developed a deeper understanding of the Russian leader and avoided characterizing his counterpart. Their talks were “good, positive,” he said, and not “strident.” They discussed their disagreements, “but it was not done in a hyperbolic atmosphere.”

Mr. Biden, who agreed this year with an interviewer that Mr. Putin was a “killer,” said on Wednesday that he had no need to discuss that further. “Why would I bring it up again?” Mr. Biden asked.

But he was palpably sensitive to criticism that he was too accommodating to Mr. Putin, a worry shared by some inside his own administration and a critique that has turned into an increasingly loud talking point by Republicans who rarely protested President Donald J. Trump’s chummy bromance with the Russian leader.

Asked as he was leaving his post-meeting news conference how he could be confident that Mr. Putin’s behavior would change, Mr. Biden whirled about and grew testy. “When did I say I was confident?” he snapped at a reporter. “I said what will change their behavior is if the rest of the world reacts to them and it diminishes their standing in the world. I’m not confident of anything. I’m just stating a fact.”

The fact that Mr. Biden and Mr. Putin offered their judgments at separate news conferences was itself a telling sign of the coolness in the relationship. Since 1989, when President George H.W. Bush and President Mikhail Gorbachev of the Soviet Union addressed reporters together after a summit meeting in Malta, joint media appearances have been the standard for American and Russian leaders.

Mr. Biden opted instead not to share a stage with the Russian leader, drawing a sharp contrast with Mr. Trump, who benefited from Russian interference in the 2016 campaign even though no illegal collusion was ever charged. With the master of the Kremlin by his side in Helsinki, Finland, in 2018, Mr. Trump memorably suggested that he trusted Mr. Putin’s denial more than American intelligence agencies that detected the election interference — a view the former president reaffirmed just last week.

Mr. Biden, by contrast, emphasized that he did not place his faith in Mr. Putin. “This is not about trust,” he said. “This is about self-interest and verification of self-interest.”

But the decision to hold the meeting at all was also a break from the previous administration Mr. Biden was a part of. After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014, President Barack Obama, with the support of Mr. Biden, then his vice president, sought to isolate Mr. Putin, throwing him out of the Group of 8 industrialized nations and refusing to meet with him.

Mr. Biden has effectively abandoned that approach, gambling that it was better to grant Mr. Putin the respect of a meeting and the stature that comes from sitting down with an American president in hopes of preventing further escalation in the conflict with Moscow. The goal is less to make the situation better than to keep it from becoming worse.

In that sense, some experts said offering the Geneva meeting may have forestalled Mr. Putin from taking more aggressive action in recent weeks, given that in the interim he pulled back at least some troops he had massed on the border with Ukraine and provided medical assistance to Aleksei A. Navalny, the imprisoned opposition leader who was said to be on the edge of death.

By appearing before cameras together only for a few moments at the beginning of their meeting, Mr. Biden and Mr. Putin gave little indication of personal chemistry. They shook hands but shared little of the body-language bonhomie that Mr. Trump did with Mr. Putin. In one small area of commonality, Mr. Biden gave a pair of his favorite aviator sunglasses to Mr. Putin, who also loves wearing shades. And Mr. Putin noted that Mr. Biden shared stories about his mother, as he often does.

They each voiced their divergent positions afterward, with Mr. Biden condemning Russian cyberattacks, international aggression and domestic oppression and Mr. Putin engaging in his typical what-about defense by citing objectionable American actions. In a truculent tone, Mr. Putin even defended his crackdown on nonviolent opposition figures like Mr. Navalny by saying he wanted to avoid an insurrection like the Jan. 6 storming of the United States Capitol, a comparison Mr. Biden called “ridiculous.” But they kept their criticisms from becoming personal.

“It was businesslike, it was professional,” said Angela E. Stent, a former national intelligence officer on Russia and author of books about Mr. Putin and the West. “Neither of them really gave ground on anything. But they seemed to have established something that could be a working relationship.”

Fiona Hill, who as Mr. Trump’s senior Russia adviser was so alarmed by his deference to Mr. Putin in Helsinki that she has said she thought about faking a medical emergency to end the session, called this meeting a marked contrast. “It just feels more professional on both sides,” she said.

While Mr. Biden is sunnier and Mr. Putin more dour, they are both seasoned political leaders under no illusions about each other. “Both of them are realists,” she said. “There’s nobody going in there with high expectations.”

Mr. Biden is only the latest in a long line of American presidents forced to figure out how to deal with Mr. Putin, a two-decade story of misjudgment, exasperation and bitterness. A onetime K.G.B. colonel who reversed Russia’s halting post-Soviet experiment with democracy and consolidated power in the hands of a small, well-heeled ruling clique, Mr. Putin has defied all manner of American charm, inducement, pressure and punishment.

President Bill Clinton was the first to interact with Mr. Putin after he became prime minister and considered him “tough enough to hold Russia together,” as he later put it in his memoir, but felt brushed off by the new leader who seemed uninterested in doing business with a departing American president.

His successor, President George W. Bush, fashioned a closer bond with Mr. Putin at first, famously declaring after their first meeting that he had gotten “a sense of his soul,” a comment he came to regret.

The two grew apart, particularly after Mr. Bush’s invasion of Iraq and Mr. Putin’s increasing suppression of internal dissent. By later years, Mr. Bush complained privately that meetings with Mr. Putin were “like arguing with an eighth-grader with his facts wrong” and told a European leader that Mr. Putin had become “a czar.” They finally broke after Russia’s invasion of the former Soviet republic of Georgia in 2008.

Mr. Obama and Mr. Biden came into office determined to “reset” relations with Russia and made some progress by negotiating a new arms control treaty and transit rights for American troops heading to Afghanistan through Russian airspace. But Mr. Obama and Mr. Putin came to disdain each other even before the Ukraine invasion, with the American mocking the Russian for having a “kind of slouch” that made him look “like that bored schoolboy in the back of the classroom.”

Mr. Trump’s relationship with Mr. Putin was most perplexing because he broke from bipartisan consensus and lavished extravagant praise on a Russian leader considered an anti-democratic, anti-American authoritarian by almost everyone else in Washington. Under pressure from Congress or his own advisers, Mr. Trump’s administration at times imposed sanctions or expelled diplomats in response to Russian provocations, but the president himself avoided publicly criticizing Mr. Putin.

Even discounting Mr. Trump, Mr. Biden arrived in Geneva with the advantage of having met with Mr. Putin before as vice president and watching his predecessors struggle with the Putin challenge. “He’s trying to synthesize all the lessons from every other president,” Ms. Hill said.

As a result, the Biden team knew how Mr. Putin tries to knock American presidents off guard by keeping them waiting or by having the last word, so it made certain to sidestep those traps in Geneva by starting the meetings on time and having Mr. Biden go second in the dueling news conferences.

“Our side now knows what the games are that Putin plays,” said Evelyn Farkas, a senior Pentagon official focused on Russia under Mr. Obama. “There are a lot of things we got smart on.”

But if Mr. Biden avoided a rupture with Mr. Putin at their first meeting, it was only the beginning of this latest chapter in Russian-American relations. “We can all wipe the sweat off our brow that we got through that one,” Ms. Hill said. “The question is what comes next.”