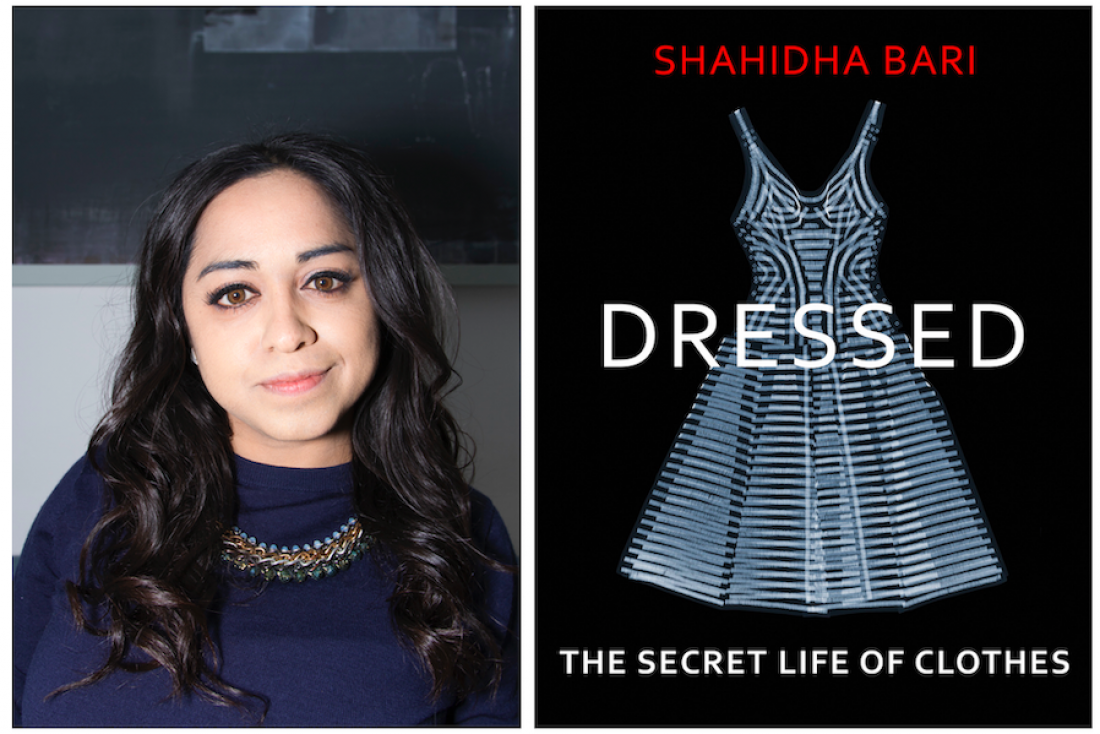

Shahidha Bari

Dear Commons Community,

Shahidha Bari has an op-ed in The Chronicle of Higher Education this morning commenting on “what we have lost in a year of virtual teaching.” She is a professor of fashion cultures and histories at London College of Fashion at the University of the Arts London, and the author of Dressed: A Philosophy of Clothes. Her basic premise is that our professional identities have suffered but so have our students. She opens the op-ed with:

“Like everyone else, I’ve been busy coming to grips with our brave new Covid-19 world, figuring out how to navigate online teaching and socially distanced campuses. Will the changes that we’ve been compelled to make over the last year have lasting effects on college and university life? It’s tempting to hope our adaptations are only temporary, but the nature of our profession may have been transformed while we were busy getting through the year.”

She goes to comment on what she has experienced and makes the point that while we may have lost something, we have learned a great deal about teaching and learning in virtual environments, all of which may be beneficial as we move forward even in our traditional face-to-face classes.

Below is her entire piece.

Tony

————————————————————————————

The Chronicle of Higher Education

What We’ve Lost in a Year of Virtual Teaching

Shahidha Bari

February 7, 2021

Late in 2020, I learned that there are two kinds of people in the world: those who have discovered the “Touch-Up My Appearance” setting on Zoom video calls and the rest of us — languishing in ignorance, unhappily bathed in harsh blue laptop light. If you weren’t already aware of the soft-focus feature on Zoom, you might like to know that it has the “flattering” effect of blending your edges and correcting your complexion until you are rendered a smooth and poreless avatar, unrecognizable to yourself and your loved ones. I came to learn of it pathetically late in the game, although to be fair there’s been a lot to learn lately.

Like everyone else, I’ve been busy coming to grips with our brave new Covid-19 world, figuring out how to navigate online teaching and socially distanced campuses. Will the changes that we’ve been compelled to make over the last year have lasting effects on college and university life? It’s tempting to hope our adaptations are only temporary, but the nature of our profession may have been transformed while we were busy getting through the year.

Take, for instance, what you’ve been wearing to work. In 2017, I wrote about academic fashion for The Chronicle Review, lightly mocking our profession’s pretensions and pointing out how what we wear signals status anxiety, income inequality, and other pitfalls of academic life. Who knew that I’d spend most of the last semester delivering seminars from my living room, barefoot and with a (mostly) clean sweater hastily paired with sweatpants? I certainly could not have predicted that my students would join me in London from time zones in Paris, Hong Kong, and Sydney, very often logging in from their childhood bedrooms. It’s astonishing how quickly you become accustomed to seeing students bundled in robes or lounging in polka-dot onesies.

I don’t blame them. There’s a lot to be said for comfort dressing during quarantine, in the sense of not only being comfortable but also wearing the kinds of garments that might give us comfort, solace, or support when we’re under duress. But the lapsed dress codes of our online teaching platforms seem to indicate something else: a tacit agreement that in these unprecedented circumstances we can allow ourselves to let go a little. Professors are forgiven for pulling on yesterday’s shirt for today’s seminar. On Zoom and Teams we roll up our grubby sleeves, push up our glasses, and collectively exhale as we try, together, simply to keep life going. And perhaps we need to continue to allow this slack — this being kind to ourselves — in workplaces that have been hectic, high pressured, and unhappy not just for the last year but for decades now.

The result of all this has been a humanization of our work. Consider the virtual department meeting: We log on from home, variously wrangling poor internet connectivity, home-schooled children, over-affectionate pets, and the mail carrier who seems to be continually banging on the door. Suddenly we see many of our colleagues as we haven’t before. And there’s a lesson in our comically housebound “professional” gatherings that isn’t simply about how we should harness technology for productivity “going forward.” What we learn instead is that the veil between work and life has been rent. No, you will never be able to unsee the sight of Professor X in his tartan boxer shorts when he gets up to answer the door midmeeting — regrettably, that is now burned into your retinas. But you might also better understand the world from which he comes, the human errors of which he is capable, and the ordinary joys, obligations, and suffering to which we are all subject.

Individually, we have always known this. We’ve always wiped the baby spit-up from our blouses as we dashed out the door, hurriedly paid the electricity bill on our lunch break, and ducked out of meetings to have time to grab a half-gallon of milk on the way home. We’ve always brought work home, grading on weekends and writing on vacations. In short, in academe work and home have never been separable. And so the shattering of our “professional” appearances isn’t some dramatic revelation but instead a blow to a collective fiction we cherish about academic conduct. Where does that collective fiction come from? Perhaps we’ve generated it ourselves — a mythmaking that begins in graduate school and accelerates as our aspirations to work in an apparently dignified and noble profession deepen. But this self-mythologizing can be unforgiving. Before the pandemic, in our more self-serious moments, we pictured ourselves smartly dressed, striding purposefully across a manicured campus lawn, trailed by worshipful students — or else monastically secluded in book-lined offices, dedicated to deep thought. Now our dreams are more modest.

Occasionally, though, we lived up to those mental images. To my mind, dressing up was part of that fiction. The simple act of putting on shoes and packing a book bag would serve to apportion my day, convincing myself I was in “professorial mode.” These rituals are not superficial. We know now how undifferentiated life can feel without the usual accoutrements. Do you remember how a tie and collar could stiffen your neck and straighten your spine, beckoning from your body the rectitude required for work? Our clothes tell us we are at work; without such cues, we might find ourselves slumping into indolence.

But the pandemic is an opportunity to shift the conversation from individual efforts to achieve a professional identity to institutional efforts to aid us in that. In lieu of self-care, the conversation could now turn to our university’s duty of care toward us, its labor force. What does it mean to properly achieve a work-life balance? Why do we hide our suffering and stress in the masquerade of seemingly effortless academic accomplishment? How could our employers have ever believed that we are simply brains and not bodies, too often tired from overwork and hungry because we didn’t have time to grab a proper lunch?

Other things have changed as well. Crucially, it seems to me, our relationship with students has been recalibrated by the mediated nature of online teaching. It’s been a challenge adapting course materials and teaching practices to virtual media, and yet I’ve found students to be patient and understanding about my relative incompetence. “You’re on mute,” they bellow, theatrically cupping their ears. “Have you tried switching it on and off again?” they type encouragingly, as the PowerPoint freezes. Teaching itself has become a more collaborative practice, in which students take the book learning I offer and give it form, color, and shape on virtual whiteboards they liberally pepper with images, commentary, hyperlinks, and yes, emojis.

The challenge is how to avoid producing just another video that makes their eyes glaze over (this, after all, is a generation of habitual screen watchers). We encourage their engagement with chats and commentaries and other ingenious mechanisms. And behind those efforts is a new acceptance of the inadequacies of the lecture format and the unquestioned power dynamics by which silent, note-taking students dutifully ingest our words. The formalities of the student-teacher relationships we grew used to may be no more. A certain mystique is lost, I concede, when your students see your overfed cat trample your keyboard and knock over your chipped Bart Simpson mug. And it’s simply impossible to exit a Zoom lecture gracefully. Believe me, I’ve tried. After I painstakingly perorate on Plato, a virtual red-velvet curtain should fall with flourish at the designated moment and cue the applause. Instead, we mumble, “that’s it,” and awkwardly fumble for the mouse before the screen freezes on our half-gaping mouths.

It’s at the moment when the screen goes blank and I’m left alone in my living room that I feel a pang. I remember all the other teaching, like when a timid student corners you at the end of a class or an eager one catches you in the corridor. Our work happens in spontaneous encounters — you remember that there’s a book about exactly the thing this student is describing and it’s right here, so you hand it over directly. There’s something heartbreaking about the silent corridors and empty classrooms of the last year. The university may not always be pretty or well maintained, but it is designed to enable encounters between thinking beings in a real place and time.

Teaching is about an attunement to actual bodies in actual space. It’s in the way we read the room for responsiveness or reluctance, adapting when we sense incomprehension, clarifying when we find confusion. It’s also about rearranging desks, sharing marked-up essays, and peering into lab equipment. Our bodies teach as well: When we stand in front of students, explaining abstract ideas and responding to their curiosity, we are presenting them with an idea of how to be a grown-up person. Things might have changed, but surely some things are still sacred to us, still worth trying to hold onto — if we ever have the chance to return to normality.

I hope that some of the changes brought about by the pandemic will have lasting consequences for academic life. But there are fundamentals that we must not lose. I think of all the discarded coffee cups that litter our lecture halls, the coats that dangle on the backs of chairs in seminar rooms, the way that students elbow for room in studios and determinedly clutter all available table space, the security officers who wait patiently at entrances while we rummage for our passes, the books that need returning, and the office plants that need watering. And I remember that colleges and universities really are meant for the meeting of minds.