Dear Commons Community.

Earlier this week, Gerry Murray, of roller derby fame died at the age of 98. I was surprised by the extensive obituary (see below) in the New York Times written about her.

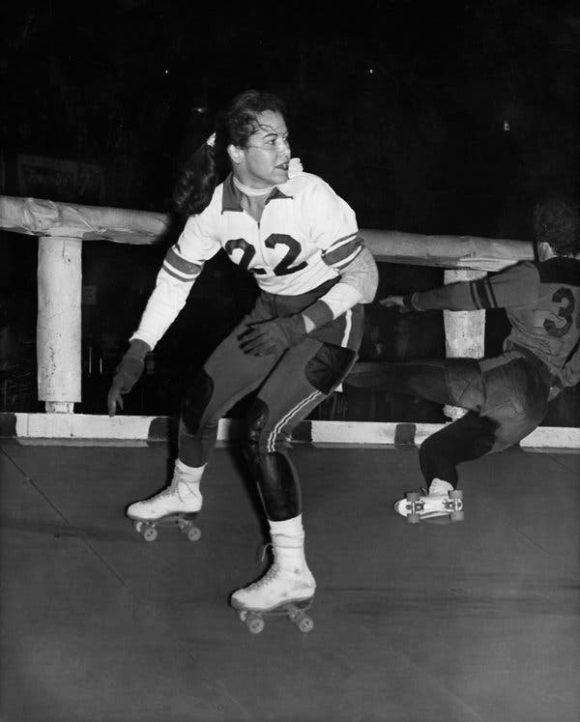

I had forgotten Gerry but as a child growing up in the Bronx in the 1950s, my brothers and I were great fans of the New York Chiefs roller derby team and especially her. She was an exciting skater who was speedy and tough. I can remember my older brother Donald taking my brother Peter and me, to see her and the Chiefs at the 69th Street Regiment Armory. She was by far the top fan favorite.

She was a small and happy part of my childhood and am glad to see that she led a long life.

Tony

———————————————————————————–

Gerry Murray, Stalwart Roller Derby Star, Dies at 98

New York Times

By Richard Sandomir

Aug. 15, 2019

Gerry Murray, an aggressive and durable roller derby star who began her career in the late 1930s — and, after retiring, resumed it in the 1970s — and whose teammates included her two husbands and her only son, died on Aug. 9 in Des Moines. She was 98.

Her granddaughter, Sharilee Cantal, confirmed the death.

Murray joined the roller derby circuit as a teenager three years after a promoter, Leo Seltzer, conceived the sport in 1935. She stayed long enough to be part of its postwar surge of popularity, which brought large crowds to arenas and millions of viewers to television sets.

An exceptionally fast skater, she could deftly dispatch rival skaters on the sport’s banked oval track by jabbing them with a sharp elbow or thrusting a hip at them.

Murray, who played for most of her career with the New York Chiefs, was “a female terror, swishing around the track at 30 miles an hour, hipping her opponents, zigzagging recklessly, her red hair, tied in a ribbon, winging along behind her,” Gay Talese wrote in The New York Times in 1958.

In a sport filled with bruising action, Murray was known for her on-track battles with other women, notably Midge (Toughie) Brasuhn of the Brooklyn Red Devils. They were two of the biggest attractions in a league where the teams consisted of both men and women — unusual then and now — and women were often the stars.

“The worst roughing up I got was in Chicago against Toughie,” Murray told the gossip columnist Earl Wilson in 1950 about the serious leg injury she incurred in one of their bruising encounters. “She gave me one of those terrific blocks and I wasn’t even expecting it. I ended up on the rail. I hit the upright in midair.”

Despite the bloody noses Murray gave Brasuhn, they were friends off the track.

Their track duels inspired Sue Macy to write a children’s book, “Roller Derby Rivals” (2014), with illustrations by Matt Collins. “It was really passionate,” Ms. Macy said in a phone interview. “They weren’t just playing at hitting each other.”

Murray had a theory about why some young women entered roller derby’s aggressive world: They were shy and not too athletic, and they had not found outlets for their latent killer instincts.

“Once unleashed on the banked track,” she was quoted by Frank Deford in his book “Five Strides on the Banked Track” (1971), “the kid wakes up and learns it’s great to bounce people off their feet and onto their heads.”

In the close-knit, self-contained roller derby world, in which teams lived together for weeks at a time in the cities where they were competing, Murray married two of her male colleagues.

With Paul Milane, she had a son, Mike. After their divorce, she married Gene Gammon, who adopted Mike and was also her coach and teammate. They later divorced.

Mike Gammon — who was fitted with roller skates at 13 months — joined the league in the late 1950s as a teenager, played with his mother on the Chiefs and became one of the sport’s top stars.

Geraldine Murray was born on Sept. 30, 1920, in Des Moines to Raymond and Leila (Zika) Murray, and was raised largely by a grandmother. As a youngster, Gerry swam, ran track and played volleyball and softball. While playing in a high school softball tournament in Chicago in 1938, a friend suggested that she try out for roller derby at a local fair grounds.

She knew how to skate, but at first she could not fathom racing around the steeply banked track used in roller derby. “Are you kidding?” she recalled thinking in an interview with the roller derby writer Alan Ebert. “I could never skate on that thing.”

But she adapted, was chosen as a trainee and went to the derby’s school in Texas.

For the next 22 years, she played for the Chiefs and other teams. She oversaw the Chiefs’ training for some of that time and occasionally used her sewing skills to mend their uniforms.

After retiring in 1960 she held various jobs, owned two bars and bought a cattle and horse ranch in Hayward Hills, in Northern California, with her son and his wife, Judi McGuire Gammon, who also skated for the Chiefs.

In addition to her son and granddaughter, she is survived by two great-grandchildren and two great-great-grandchildren.

In 1975, she returned to skating. Her old league had shut down two years earlier so, in her mid-50s, she joined the New York Braves of the new United Banked Track Skating Association, which led to newspaper headlines like “What’s a Nice Grandma Doing on Skates?” Her teammates included her son and daughter-in-law.

She was serious about returning, although she recognized why others would question her motives.

“This isn’t a publicity stunt,” she told United Press International. “If I can’t skate and skate the right way, I don’t want to skate at all.”

The league collapsed quickly, but in 1977 she tried again, joining a reconstituted Chiefs squad in the International Roller Skating League. In one match that season, Murray blocked and elbowed a rival, Carol (Peanuts) Meyer of the San Francisco Bay Bombers, with the physical vigor of her much younger self.

But that would be her final season. While skating in San Jose, she was knocked into a rail, broke a rib and punctured a lung.

Advertisement

“She was hospitalized for two or three days but skated the rest of that season,” Donald Drewry, a founder of the International Roller Skating League and a roller derby announcer, said in a phone interview. “She never told management, but when they found out, they were afraid to let her skate any longer.”

She retired, again, to her ranch, then returned to Des Moines in the 1990s.