Dear Commons Community,

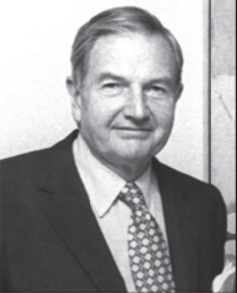

David Rockefeller, the last surviving son of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. died yesterday at the age of 101 at his home in Pocantico Hills. I lived in Pocantico Hills for thirty-seven years just across the road from the north edge of the Rockefeller Estate (now the Rockefeller State Park) and on several occasions had conversations with Mr. Rockefeller through my work as a volunteer firefighter and a member of the local Board of Education. While a titan of banking and philanthropy, I found him to be a regular person and “neighbor”. The last time I spoke with him was in 2004 when he invited a small group of firefighters who had responded to an alarm at the Stone Barns, a portion of his property that he was converting into an Education Center as a memorial for his wife Peggy. He hosted a small cocktail party for about fifteen people, mostly fellow volunteer firefighters. His living room was quite comfortable with a pile of old newspapers collecting in one corner and a large, floppy couch with an incredible view of the Palisades. There were also a number of Monets on the walls of which he was quite proud and spoke to us about. In a discussion I had with him about his autobiography, Memoirs, which I had read and was published in 2002, he gave me a detailed description of the Shah of Iran affair in the late 1970s that preceded the taking of American hostages. It was quite an interesting evening. Mr. Rockefeller could not have been more gracious and welcoming. On a another ocassion, I had the privilege of introducing him as the main speaker at a Memorial Day Parade. When I contacted him to ask if there was anything that he would like me to mention as part of the introduction, he said “to just introduce him as our neighbor of seventy years”.

His complete New York Times obituary is below.

Tony

David Rockefeller, Philanthropist and Head of Chase Manhattan, Dies at 101

David Rockefeller, the banker and philanthropist with the fabled family name who controlled Chase Manhattan bank for more than a decade and wielded vast influence around the world for even longer as he spread the gospel of American capitalism, died on Monday morning at his home in Pocantico Hills, N.Y. He was 101. A family spokesman, Fraser P. Seitel, confirmed the death.

Chase Manhattan had long been known as the Rockefeller bank, although the family never owned more than 5 percent of its shares. But Mr. Rockefeller was more than a steward. As chairman and chief executive throughout the 1970s, he made it “David’s bank,” as many called it, expanding its operations internationally.

His stature was greater than any corporate title might convey, however. His influence was felt in Washington and foreign capitals, in the corridors of New York City government, in art museums, in great universities and in public schools.

Mr. Rockefeller could well be the last of a less and less visible family to have cut so imposing a figure on the world stage. As a peripatetic advocate of the economic interests of the United States and of his own bank, he was a force in global financial affairs and in his country’s foreign policy. He was received in foreign capitals with the honors accorded a chief of state.

He was the last surviving grandson of John D. Rockefeller, the tycoon who founded the Standard Oil Company in the 19th century and built a fortune that made him America’s first billionaire and his family one of the richest and most powerful in the nation’s history.

As an heir to that legacy, David Rockefeller lived all his life in baronial splendor and privilege, whether in Manhattan (when he was a boy, he and his brothers would roller skate along Fifth Avenue trailed by a limousine in case they grew tired) or at his magnificent country estates.

Imbued with the understated manners of the East Coast elite, he loomed large in the upper reaches of a New York social world of glittering black-tie galas. His philanthropy was monumental, and so was his art collection, a museumlike repository of some 15,000 pieces, many of them masterpieces, some lining the walls of his offices 56 floors above the streets at Rockefeller Center, to which he repaired, robust and active, well into his 90s.

In silent testimony to his power and reach was his Rolodex, a catalog of some 150,000 names of people he had met as a banker-statesman. It required a room of its own beside his office.

Spread out below that corporate aerie was a city he loved and influenced mightily. He was instrumental in rallying the private sector to help resolve New York City’s fiscal crisis in the mid-1970s. As chairman of the Museum of Modern Art for many years — his mother had helped found it in 1929 — he led an effort to encourage corporations to buy and display art in their office buildings and to subsidize local museums. And as chairman of the New York City Partnership, a coalition of business executives, he fostered innovation in public schools and the development of thousands of apartments for lower-income and middle-class families.

He was always aware of the mystique surrounding the Rockefeller name.

“I have never found it a hindrance,” he once said with typical reserve. “Obviously, there are times when I’m aware that I’m treated differently. There’s no question that having financial resources, which, thanks to my parents, I learned to use with some restraint and discretion, is a big advantage.”

An Ambassador for Business

With his powerful name and his zeal for foreign travel — he was still going to Europe into his late 90s — Mr. Rockefeller was a formidable marketing force. In the 1970s, his meetings with Anwar el-Sadat of Egypt, Leonid Brezhnev of the Soviet Union and Zhou Enlai of China helped Chase Manhattan become the first American bank with operations in those countries.

“Few people in this country have met as many leaders as I have,” he said.

Some faulted him for spending so much time abroad. He was accused of neglecting his responsibilities at Chase and failing to promote aggressive, visionary managers. Under his leadership, Chase fell far behind its rival Citibank, then the nation’s largest bank, in assets and earnings. There were years when Chase had the most troubled loan portfolio among major American banks.

“In my judgment, he will not go down in history as a great banker,” John J. McCloy, a Rockefeller friend and himself a former Chase chairman, told The Associated Press in 1981. “He will go down as a real personality, as a distinguished and loyal member of the community.”

Mr. Rockefeller’s forays into international politics also drew criticism, notably in 1979, when he and former Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger persuaded President Jimmy Carter to admit the recently deposed shah of Iran into the United States for cancer treatment. The shah’s arrival in New York enraged revolutionary followers of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, provoking them to seize the United States Embassy in Iran and hold American diplomats hostage for more than a year. Mr. Rockefeller was also assailed for befriending autocratic foreign leaders in an effort to establish and expand his bank’s presence in their countries.

“He spent his life in the club of the ruling class and was loyal to members of the club, no matter what they did,” the New York Times columnist David Brooks wrote in 2002, citing the profitable deals Mr. Rockefeller had cut with “oil-rich dictators,” “Soviet party bosses” and “Chinese perpetrators of the Cultural Revolution.”

Still, presidents as ideologically different as Mr. Carter and Richard M. Nixon offered him the post of Treasury secretary. He turned them both down.

After the death in 1979 of his older brother Nelson A. Rockefeller, the former vice president and four-term governor of New York, David Rockefeller stood almost alone as a member of the family with an outsize national profile. Only Jay Rockefeller, a great-grandson of John D. Rockefeller, had earned prominence, as a governor and United States senator from West Virginia. No one from the family’s younger generations has attained or perhaps aspired to David Rockefeller’s stature.

“No one can step into his shoes,” Warren T. Lindquist, a longtime friend, told The Times in 1995, “not because they aren’t good, smart, talented people, but because it’s just a different world.”

A Privileged Life

The youngest of six siblings, David Rockefeller was born in Manhattan on June 12, 1915. His father, John D. Rockefeller Jr., the only son of the oil titan, devoted his life to philanthropy. His mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, was the daughter of Nelson Aldrich, a wealthy senator from Rhode Island.

Besides Nelson, born in 1908, the other children were Abby, who was born in 1903 and died in 1976 after leading a private life; John D. Rockefeller III, who was born in 1906 and immersed himself in philanthropy until his death in an automobile accident in 1978; Laurance, born in 1910, who was an environmentalist and died in 2004; and Winthrop, born in 1912, who was governor of Arkansas and died in 1973.

David grew up in a mansion at 10 West 54th Street, the largest private residence in the city at the time. It bustled with valets, parlor maids, nurses and chambermaids. For dinner every night, his father dressed in black tie and his mother in a formal gown.

Summers were spent at the 107-room Rockefeller “cottage” in Seal Harbor, Me., and weekends at Kykuit, the family’s country compound north of New York City in Tarrytown, N.Y. The estate was likened to a feudal fief. As Mr. Rockefeller wrote in his autobiography, “Memoirs” (2002), “Eventually the family accumulated about 3,400 acres that surrounded and included almost all of the little village of Pocantico Hills, where most of the residents worked for the family and lived in houses owned by Grandfather.”

In that bucolic setting, he developed a fascination for insects that would lead to his building one of the largest beetle collections in the world.

David was 21 when John D. Rockefeller died. “He told amusing stories and sang little ditties,” Mr. Rockefeller recalled in 2002. “He gave us dimes.”

Mr. Rockefeller’s sense of noblesse oblige was heightened by his early education at the experimental Lincoln School in Manhattan, founded by the American philosopher John Dewey and financed by the Rockefeller Foundation to bring together children from varied social backgrounds. He went on to study at Harvard, receiving his bachelor’s degree in 1936, and then spent a year at the London School of Economics, a hotbed of socialist intellectuals. Mr. Rockefeller was awarded a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago in 1940.

Moved by the Great Depression at home and abroad, he stated in his doctoral thesis that he was “inclined to agree with the New Deal that deficit financing during depressions, other things being equal, is a help to recovery.” The notion that a Rockefeller would take such a liberal economic view was major news; the family, rock-ribbed Republican, was known for its fierce opposition to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the New Deal’s author.

After receiving his doctorate, Mr. Rockefeller became a secretary to Fiorello H. La Guardia, New York’s pugnacious, liberal Republican mayor. In 1940, he married Margaret McGrath, known as Peggy, whom he had met at a dance seven years earlier, when he was a Harvard freshman and she was a student at the Chapin School in New York. His wife, a dedicated conservationist, died at 80 in 1996. They had six children: David Jr., Abby, Neva, Margaret, Richard and Eileen. A complete list of his survivors was not immediately available.

Mr. Rockefeller enlisted in the Army in 1942, attended officer training school and served in North Africa and France during World War II. He was discharged a captain in 1945.

He began his banking career in 1946 as an assistant manager with the Chase National Bank, which merged in 1955 with the Bank of Manhattan Company to become Chase Manhattan.

Banking in the early postwar era was a gentleman’s profession. Top executives could attend to outside interests, using social contacts to cultivate clients while leaving day-to-day management to junior officers.

Mr. Rockefeller found plenty of time for such activities. In the late 1940s, he replaced his mother on the Museum of Modern Art’s board and eventually became its chairman. He courted art collectors. In 1968, he put together a syndicate, including his brother Nelson and the CBS chairman, William S. Paley, to buy Gertrude Stein’s collection of modern art. David and Peggy Rockefeller’s own prized paintings — by Cézanne, Gauguin, Matisse, Picasso — were lent to the museum permanently.

Putting a Bank in Order

Mr. Rockefeller’s rise in banking was swift. By 1961, he was president of Chase Manhattan and its co-chief executive with George Champion, the chairman. Promoting expansion overseas, Mr. Rockefeller clashed with Mr. Champion, who thought that the bank’s domestic business was more important. After Mr. Rockefeller replaced Mr. Champion as chairman and sole chief executive in 1969, he was able to enlarge the bank’s presence on almost every continent. He said his brand of personal diplomacy, meeting with heads of state, was crucial in furthering Chase’s interests.

“There were many who claimed these activities were inappropriate and interfered with my bank responsibilities,” Mr. Rockefeller wrote in his autobiography. “I couldn’t disagree more.” His “so-called outside activities,” he insisted, “were of considerable benefit to the bank both financially and in terms of its prestige around the world.”

By 1976, Chase Manhattan’s international arm was contributing 80 percent of the bank’s $105 million in operating profit. But instead of vindicating Mr. Rockefeller’s avidity for banking abroad, those figures underlined Chase’s lagging performance at home. From 1974 to 1976, its earnings fell 36 percent while those of its biggest rivals — Bank of America, Citibank, Manufacturers Hanover and J.P. Morgan — rose 12 to 31 percent.

The 1974 recession hammered Chase, which had an unusually large portfolio of loans in the depressed real estate industry. It also owned more New York-related securities than any other bank in the mid-1970s, when the city was edging toward bankruptcy. And among major banks, Chase had the largest portfolio of nonperforming loans.

Chase also got caught up in a scandal in 1974. An internal audit discovered that its bond trading account was overvalued by $34 million and that losses had been understated. A resulting $15 million drain in net income tarnished the bank’s image. In 1975, the Federal Reserve and the comptroller of the currency branded Chase a “problem” bank.

Even as he struggled to reverse Chase Manhattan’s decline, Mr. Rockefeller found time to address New York City’s financial problems. His involvement in municipal affairs dated to the early 1960s, when, as founder and chairman of the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association, he recommended that a World Trade Center be built.

In 1961, largely at his instigation, Chase opened its 64-story headquarters in the Wall Street area, a huge investment that helped revitalize the financial district and encouraged the World Trade Center project to proceed.

In the mid-1970s, with New York City facing a default on its debts because of sluggish economic growth and uncontrolled municipal spending, Mr. Rockefeller helped bring together federal, state and city officials with New York business leaders to work out an economic plan that eventually pulled the city out of its crisis.

At the same time, he put his bank’s affairs in order. By 1981, he and his protégé Willard C. Butcher had restored Chase Manhattan to full health. He yielded his chairmanship to Mr. Butcher that year.

From 1976 to 1980, the bank’s earnings more than doubled, and it outperformed its archrival, Citibank, in returns on assets, a critical indicator of a bank’s profitability. Even after retiring from active management in 1981, Mr. Rockefeller continued to serve Chase as chairman of its international advisory council and to act as the bank’s foreign diplomat. He did not hesitate to criticize United States officials for policies he considered mistaken.

He was notably harsh about President Carter. In 1980, he told The Washington Post that Mr. Carter had not done “what most other countries do themselves, and expect us to do — namely, to make U.S. national interests our prime international objective.”

But Mr. Rockefeller also played the gadfly to Mr. Carter’s far more conservative successor, President Ronald Reagan. While the Reagan administration was supporting anti-Marxist guerrillas in Africa, Mr. Rockefeller took a 10-nation tour of the continent in 1982 and declared that African Marxism was not a threat to the United States or to American business interests.

Late in life, Mr. Rockefeller was involved in controversies over Rockefeller Center, the Art Deco office building complex his father built in the 1930s. In 1985, the Rockefeller family mortgaged the property for $1.3 billion, pocketing an estimated $300 million. In 1989, the family sold 51 percent of the Rockefeller Group, which owned Rockefeller Center and other buildings, to the Mitsubishi Estate Company of Japan. Mitsubishi later increased its share to 80 percent.

The purchase represented the high tide of a buying spree of American properties by Japanese corporations, and it opened the family to criticism that it had surrendered an important national symbol to them. When Japan’s economic bubble burst in the early 1990s and Mitsubishi was forced to declare Rockefeller Center in bankruptcy in 1995, Mr. Rockefeller was criticized again, this time for allowing the site to slip into financial ruin.

Before the year ended, Mr. Rockefeller put together a syndicate that bought control of Rockefeller Center. Then, in 2000, it was sold in a $1.85 billion deal that severed the center’s last ties with the Rockefeller family.

As an octogenarian, Mr. Rockefeller, whose fortune was estimated in 2012 at $2.7 billion, increasingly devoted himself to philanthropy, donating tens of millions of dollars in particular to Harvard, the Museum of Modern Art and the Rockefeller University, which John D. Rockefeller Sr. founded in 1901.

Even in his 90s, David Rockefeller continued to work at a pace that would tire a much younger person. He spent more than half the year traveling on behalf of Chase or groups like the Council on Foreign Relations and the Trilateral Commission. In 2005, when he was interviewed in his offices at Rockefeller Center, he remained physically active, working with a trainer at the center’s sports club.

He continued to collect art, including hundreds of paintings as well as furniture and works in colored glass, porcelain and petrified wood.

That same year, he pledged a $100 million bequest to the Museum of Modern Art. Such giving became grist for the society pages. One celebrity-filled fund-raising gala at the museum in 2005 drew 850 people paying as much as $90,000 for a table. The occasion was Mr. Rockefeller’s 90th birthday, and at the end of the evening, he was presented with a birthday cake modeled after his house in Maine. Then it was off to a week in southern France to continue the celebration with 21 members of his family.

With the book “Memoirs” in 2002, he became, at age 87, the first in three generations of Rockefellers to publish an autobiography. Asked why he wrote it, he replied in his characteristic reserved tone, “Well, it just occurred to me that I had led a rather interesting life.”