As reported by Inside Higher Education: “…researchers were quick to voice their concerns about the study, particularly for its deviation from online enrollment numbers reported by the federal government’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS).

Hoxby writes that, in 2013, the proportion of students taking all or a substantial number of their courses online totaled only 7 percent of postsecondary enrollment in the U.S. Researchers at the WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies (WCET), however, found in their own analysis of IPEDS data that 27 percent of all students took at least one online course in fall 2013, and 13 percent studied exclusively online.

Since about 20 million students were enrolled at colleges and universities in the U.S. in fall 2013, Hoxby’s study counts about 1.2 million fewer students than WCET found studied exclusively online, and potentially hundreds of thousands fewer who studied partially online, said Russell Poulin, director of policy and analysis for WCET.

“Even a quick check with one of the databases they did use … would show they are off on their counts and should have made them rethink their assumptions,” Poulin said in an email.

Jeff Seaman, co-director of the Babson Survey Research Group, called the methodology “seriously flawed.” The Babson Group previously produced annual reports on the size of the online education market but began to focus more on in-depth surveys after the federal government began collecting and reporting online enrollment data.

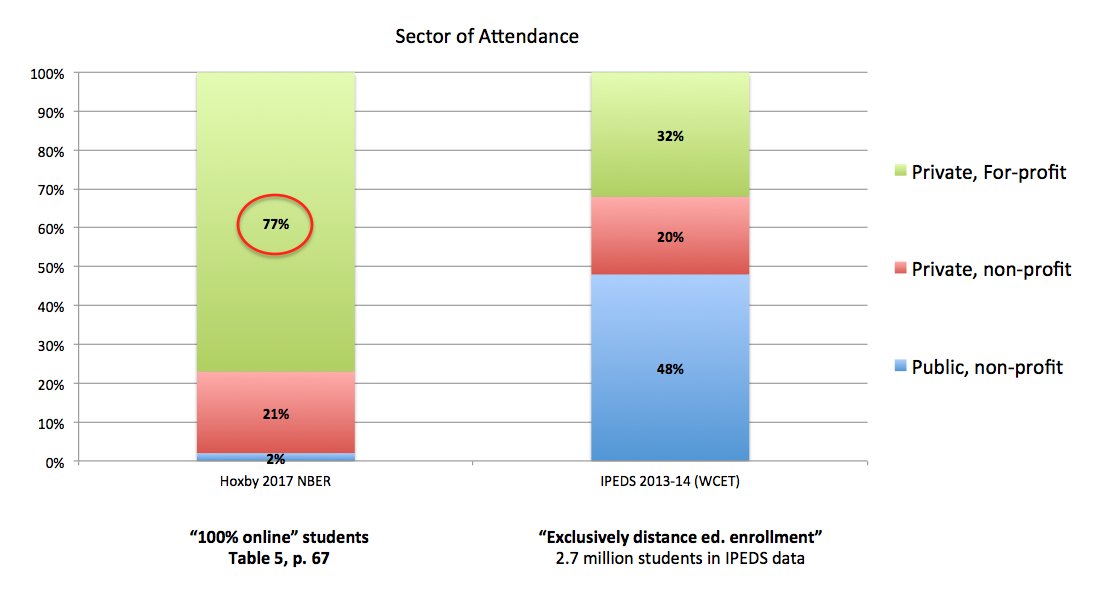

In an email, Seaman pointed to the paper’s breakdown of students who attended for-profit and nonprofit institutions as one example. Hoxby’s combination of enrollment and tax data added up to a finding that 76.8 percent of the students who studied exclusively online during the 2013-14 academic year were enrolled at for-profit colleges. IPEDS data on its own, however, found that share was only 31.9 percent.

Sean Gallagher, executive professor of educational policy at Northeastern University, summarized the discrepancy in a tweet.

“To apply different data to the problem is laudable, but not if the application of her approximations yield results that do not match the simplest of reliability checks (i.e., the estimated numbers do not match those reported in IPEDS),” Seaman wrote. “The choice of time period to examine also targets the peak of the for-profit enrollment bubble — which has now busted. So even if the methodology were not so flawed, this would still not reflect the current reality.”

Enrollment at for-profit colleges has continued to decline since 2014.

IPEDS, it should be mentioned, has its own issues. A 2014 study found that confusing guidelines and inflexible design led to several colleges greatly under- or overreporting the number of students studying online, concluding that IPEDS provided an inaccurate picture of the higher education landscape.

Phil Hill, a higher education consultant who worked on that study, called Hoxby’s paper a “hot mess.”

In a blog post, Hill said the paper’s “fundamental flaw” is that it attempts to translate institution-level data into student-level data, which causes it to not count online students enrolled at institutions that also offer face-to-face programs — Pennsylvania State University and its World Campus, for example. That’s a significant reason why the Hoxby paper so significantly understates the number of online students, among numerous things that he says renders the paper “deeply flawed.”

Hoxby did not respond to a request for comment.

Throughout the paper, Hoxby examines the personal return on investment for students who study exclusively and substantially (generally defined as taking half or more of their courses) online, and how their actions affect the return on investment for taxpayers.

To test whether online education boosts earnings, the paper focused on students who were enrolled for three calendar years — enough time for someone to earn an associate or master’s degree, or finish a bachelor’s degree (if the student transferred with previously earned college credit). Students who studied exclusively online saw their earnings grow by $853 on average in the years following that three-year enrollment period, while students who studied partly online and partly in person saw a slightly larger increase: $1,670 a year.

A majority of the students in the study were enrolled for shorter periods of time. For those students, earnings growth was much lower — a few hundred dollars a year.

Over all, the growth was not enough to cover what society paid as part of funding the educational programs, and in some cases not even the loans the students took out to enroll. The paper found that online students made disproportionate use of deductions and tax credits to fund their education, leaving taxpayers with having funded 36 to 44 percent of their education even if students repaid their student loans in full.

“This failure to cover social costs is important for taxpayers, especially for federal taxpayers, who are the main funders of online education apart from the students themselves,” the paper reads. “The failure implies that federal income tax revenues associated with future increased earnings could not come close to repaying current taxpayers.”

While students who studied online were slightly more likely to move into rapidly growing industries as a result, the paper did not find any evidence to suggest online education helps students land jobs that require abstract thinking or cutting-edge technology skills.

The paper also suggested whatever savings colleges generate by only offering online education are erased when other costs such as faculty and student support are added. Fully online colleges spent less on instruction per full-time-equivalent student — $2,334 — than colleges that also offered some face-to-face education ($3,821). But the gap nearly closed when including other core expenses ($5,991 versus $6,559). Nonselective colleges that offered hardly any online education were in the same ballpark: $5,721 per full-time-equivalent student.

Students, however, on average paid more in tuition to study online, the study found: $6,131 for students in fully online programs and $6,758 for those who took most but not all of their courses online. In comparison, students at nonexclusive colleges studying mostly in person paid an average of $4,919.

“Over all, the main contribution of this study may be to ground the discussion of online postsecondary education in evidence,” the paper reads. “Much of the discussion to this point may suffer from undue optimism or pessimism because such evidence has been lacking.”

But the initial reaction the paper has received about the evidence on which Hoxby bases her argument may temper that likelihood.”

Jeff Seaman knows more about the extent of online education than probably any other researcher in the country. He has tracked this issue nationally for more than a dozen years. I tend to support what he says about the weaknesses in the methodology of the study.

Tony