Dear Commons Community,

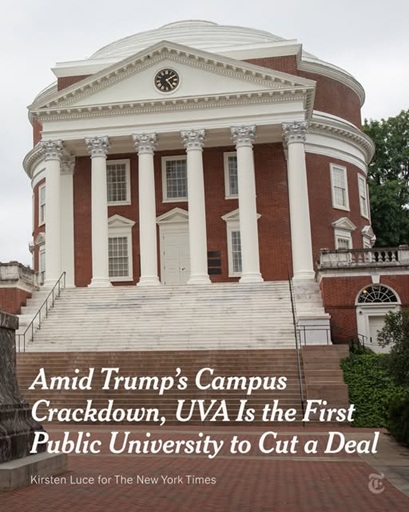

The University of Virginia yesterday reached an agreement with the Trump administration to suspend five investigations into allegations that the university’s diversity policies and programs violated civil-rights law. As reported by The Chronicle of Higher Education.

In a community message, Paul G. Mahoney, the interim president, announced that through 2028, UVa will send the U.S. Department of Justice quarterly updates on its efforts to comply with federal law and to “apply July 2025 Justice Department guidance as relevant, to the extent consistent with judicial decisions.”

That guidance articulates the Trump administration’s broad view of the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision to ban race-conscious admissions, arguing that it should be interpreted to outlaw a wide range of practices that reference race or identity. (The ruling itself only mentions admissions policies.)

The university did not agree to external monitoring, and Mahoney assured community members that UVa would not be disadvantaged in competing for federal funding. Additionally, UVa did not admit to violating the law.

“We will also redouble our commitment to the principles of academic freedom, ideological diversity, free expression, and the unyielding pursuit of ‘truth, wherever it may lead,’ as Thomas Jefferson put it,” Mahoney wrote, referencing UVa’s founder.

In return, the Justice Department is suspending its probe of UVa, which resulted, most notably, in the resignation of James E. Ryan as president in June. Unlike Columbia and Brown Universities, which struck deals with the government earlier this year, UVa will not have to pay money to the government or an outside entity.

Ryan, who had been UVa’s president since 2018, oversaw a significant expansion of its DEI efforts, which drew the attention of federal officials when Trump retook office in January. Though UVa closed its central diversity office in March, the Department of Justice accused UVa the following month of failing to fully stamp out practices that the government believed to be discriminatory. A band of conservative alumni in and outside of the Trump administration insisted Ryan step down, and when he did, Ryan characterized his decision as important for preserving jobs and grants at UVa.

According to the Trump administration, UVa will have to make more changes to curtail its DEI programs: A Justice Department statement said that if the university “completes its planned reforms prohibiting DEI … the department will close its investigations.”

If the DOJ finds UVa isn’t making sufficient progress in complying with the law, the university will have 15 days to fix problems. After that, if the DOJ still is not satisfied or if the university and the department encounter a conflict, the government can end the agreement and restart its investigations.

The federal government has also reached agreements with Brown and Columbia Universities and the University of Pennsylvania to resolve investigations into their adherence with civil-rights law. Negotiations with Harvard University and the University of California at Los Angeles have hit roadblocks.

UVa was one of nine campuses initially asked to review the Trump administration’s “Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education,” which offered institutions preferential access to federal funding if they made a series of Trump-aligned changes to their operations. UVa declined to sign the compact, as did six others in that first pool.

In a statement after The New York Times reported Tuesday that UVa and the Justice Department were nearing a deal, the co-chairs of Wahoos4UVA, an activist group that opposes the Trump administration’s involvement in university affairs, wrote that the proposed settlement was “far worse” than the compact.

“It is a capitulation to a regressive ideology that significantly oversteps what is required by law,” wrote Ann Brown and Chris Ford, both alumni. “It places into existence a permanent compliance regime with ongoing federal oversight, and without judicial review, public accountability, or the protections of due process.”

Reaction to the UVA deal on social media was fast and furious. Here is a sample.

“Another shakedown by these fascist goons,” SUNY Oswego professor Dan Baldassarre wrote on X.

“What a bunch of cowards,” former radio journalist Greg Hernandez wrote on Bluesky.

“Add the University of Virginia to the list willingly succumbing to Fascism,” Joan Resnick Ehrlich wrote on Bluesky.

“Do not attend the University of Virginia. Any university that bends the knee doesn’t deserve your attendance,” one wrote on Bluesky.

“Avoid the University of Virginia at all costs,” another wrote on Bluesky.

“Now the University of Virginia has to live with their mediocrity in bowing down to Trump’s authoritarianism,” another person wrote on Bluesky.

Tony