Click on to enlarge. M. Hersher/Science.

Click on to enlarge. M. Hersher/Science.

Dear Commons Community,

This week’s Science has an essay that revisits the legacy of Western science and research and its colonial influences. Those of us in academia who engage in research need to be reminded of the theme of this essay. Here is an excerpt.

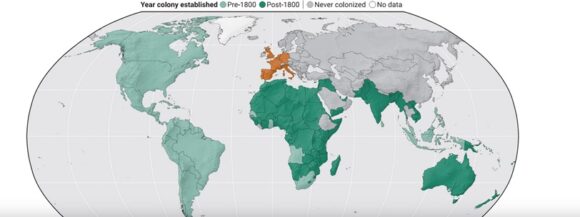

“Science—meaning the Western tradition of testing hypotheses and writing research papers—has its roots in the Enlightenment of 17th and 18th century Europe. When this new way to understand the natural world emerged, colonialism was already well established, with a handful of nations in Western Europe exerting political and economic control over distant lands and peoples. Eventually, just eight nations (the United Kingdom, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, and Italy) claimed more than half the globe.

The colonizers enslaved millions and wrung precious metals, spices, and other wealth from colonies. They also extracted specimens that form the foundation of much of modern biology. The rich natural history collections in London and Paris were born of empire. Charles Darwin’s revolutionary ideas about evolution sprang from travel aboard the HMS Beagle, a voyage intended to survey South America’s coast to further British interests.

The scientific enterprise both fueled, and was fueled by, the colonial one. For example, 19th century European scientists isolated the antimalarial compound quinine from the bark of the cinchona tree, building on what local people in Peru already knew about its medicinal properties. Europeans then used quinine to boost the health of colonial troops.

Today, the smudged fingerprints of colonization still linger on the scientific enterprise. The lingua franca of research is English. Top scientists—those with the most cited papers—disproportionately work in former colonizing nations or in a few former colonies including the United States. For decades, researchers have benefited from dropping in on former colonies to study their flora, fauna, and sometimes people, often with little involvement by local scientists and little credit to their work or intellectual property. Such “parachute science” is still with us: In 2019, for example, a study found that fewer than half of papers on infectious diseases in Africa had an African first author. Many paleontology papers from the past 34 years have no authors at all from the nations where fossils were unearthed. The nomenclature is rife with names from a racist colonial past, and even recently bestowed names disproportionately honor people from the Global North.

Scientists around the world are slowly beginning to recognize— and rectify—this colonial legacy. They are repatriating specimens, building equitable partnerships, and expanding access to the latest technologies. Researchers in once-colonized nations are taking control, using local funding and talent to explore questions they care about. Indigenous scientists are demanding respect for their traditional knowledge.”

The article concludes:

“Colonialism was an active force for 500 years, and shifting the axis of scientific influence won’t happen overnight. It will require scientists in the Global North to commit to decolonizing their work and for those in the Global South to claim their rightful places in research.”

Tony