Dear Commons Community,

The University of California and academic workers announced a tentative labor agreement yesterday, signaling a potential end to a high-profile strike that has disrupted the prestigious, 10-campus public university system for more than a month. As reported by The New York Times.

The deal promises to substantially increase pay for some 36,000 unionized workers, including teaching assistants, researchers and tutors, many of whom are graduate students. The lowest paid academic student employees, who currently start at about $23,000 in an academic year, would see salary boosts of more than 55 percent over the next two and a half years, with additional increases at campuses in Los Angeles and the Bay Area, where housing is particularly expensive. They would also receive significant increases in health and child care benefits.

Union and university officials expressed optimism about the deal, although it still must be ratified by the rank-and-file of two fractious bargaining units of the United Auto Workers, the union that represents the academic employees.

The agreement is “a huge deal, and it will go a long way toward addressing the high cost of living near U.C. campuses,” said Rafael Jaime, a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the president of a bargaining unit that represents roughly 19,000 teaching assistants, tutors and other classroom workers.

Gov. Gavin Newsom, in an interview, said he was “relieved” by the deal, but called the labor friction “a preview of things to come” as the economy softens. A state budget agreement this year that guaranteed at least five years of annual increases to U.C. funding will most likely pay for the added costs of the new contracts, he said.

“I’m pleased,” Mr. Newsom said. “I don’t expect, and hope not to see, a tuition increase.”

The announcement came as concerns had begun to mount that fall grades might be delayed by the university’s dispute with the employees who, in many ways, serve as the backbone of day-to-day undergraduate instruction. Many programs had already made adjustments to their grading schedules as the finals period and winter recess approached, but officials noted that for some students, a long postponement could jeopardize federal financial aid.

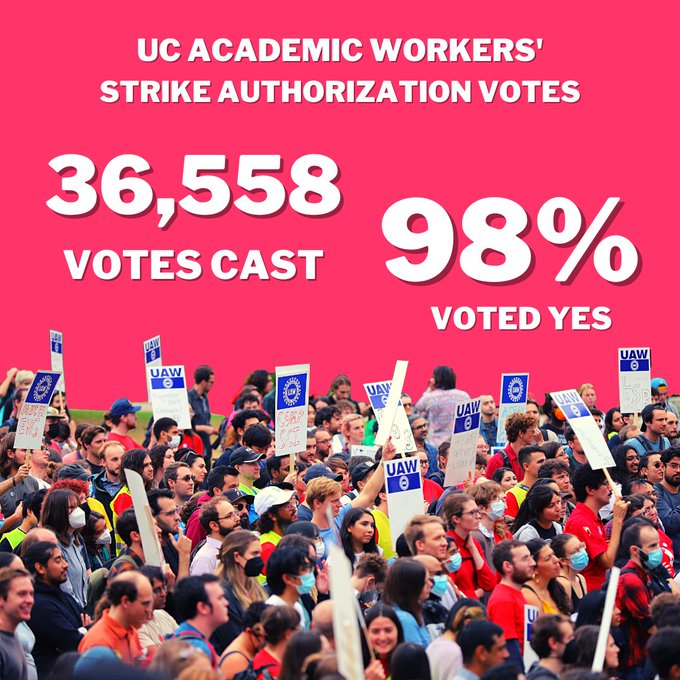

The University of California system has nearly 300,000 students and serves as the major research engine for a state that is crucial to the nation’s most innovative sectors. The labor action highlighted the schools’ reliance on the graduate students, researchers and postdoctoral fellows who lead discussion units, provide office hours, grade tests and staff research labs. The work stoppage was among the largest in the nation in an era of American workplace upheaval, and, according to the U.A.W., the largest at a university in U.S. history.

In a statement, Michael V. Drake, president of the University of California, called the tentative deal “a positive step forward” that would restore a work force that is integral to the university and its students. “These agreements will place our graduate student employees among the best supported in public higher education,” he said.

Late last month, the university reached separate five-year agreements with two other bargaining units representing about 12,000 academic researchers and postdoctoral employees, generally more senior workers whose pay was underwritten by research grants and federal funding. But that deal still left three-quarters of the striking employees without an agreement.

Darrell Steinberg, the mayor of Sacramento and a lawyer with degrees from two U.C. campuses, negotiated the deal this week at Sacramento City Hall, shuttling between rooms of union and university officials. He said that the union “fought hard to ensure that the university’s graduate students make a living wage at every campus community,” and that President Drake had created “a model for other universities throughout the country.”

Union activity has surged nationally this year as workers have leveraged bargaining power in a tight labor market, involving large retail companies such as Starbucks and Amazon, as well as private college campuses. This month, a stalemate between rail companies and unionized workers threatened freight deliveries during the holiday season until Congress and President Biden imposed a labor agreement by invoking constitutional powers that had not been used in decades.

Organized labor membership has been declining for generations, and only about 10 percent of American workers are represented by a union, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But polls this year have shown popular support for organized labor at its highest point since the mid-1960s, with approval from roughly 70 percent of Americans.

Labor leaders said the University of California strike reflected both a generational milestone and increased resistance in an economy that has become ever-reliant on intellectual labor.

“This is indicative of a kind of new excitement and empowerment, especially among younger workers who haven’t traditionally been thought of as union members,” said Lorena Gonzalez, the chief officer of the California Labor Federation, in an interview this month. She noted the involvement of “people who are going into professional fields, and who are taking this experience with them into science or technology or academia.”

“We saw a little of it around internships a few years ago,” added Ms. Gonzalez, a former Democratic state lawmaker who wrote bills that would have allowed state legislative staff to unionize. “That idea of, ‘You’re just lucky to be here’ is going by the wayside. Work is work. You can’t glorify unfair compensation just by suggesting that this is the way it has always been.”

The U.C. workers had said that their compensation fell far short of what they needed to make ends meet in California, especially given the pressures of inflation and a persistent housing shortage. Largely graduate students, they charged that the university’s business model had gone from being exploitative to untenable.

Good settlement!

Tony