Dear Commons Community,

Last fall, male undergraduate enrollment fell by nearly 7 percent, nearly three times as much as female enrollment, according to the National Student Clearinghouse. The decline was the steepest — and the gender gap the largest — among students of color attending community colleges. Black and Hispanic male enrollment at public two-year colleges plummeted by 19.2 and 16.6 percent, respectively, about 10 percentage points more than the drops in Black and Hispanic female enrollment. Drops in enrollment of Asian men were smaller, but still about eight times as great as declines in Asian women. As reported in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

“Men as a whole aren’t usually the group that comes to mind as needing a leg up. But for colleges, declining male enrollment means less revenue and less viewpoint diversity in the classroom. For the economy, it means fewer workers to fill an increasing number of jobs that require at least some college education, and a future in which the work force is split even more along gender lines.

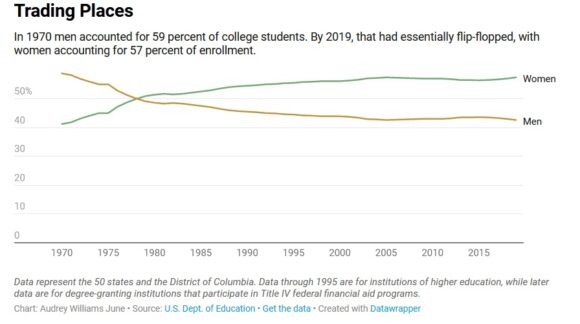

In the late 1970s, men and women attended college in almost equal numbers. Today, women account for 57 percent of enrollment and an even greater share of degrees, especially at the level of master’s and above. The explanations for this growing gender imbalance vary from the academic to the social to the economic. Girls, on average, do better in primary and secondary school. Boys are less likely to seek help when they struggle. And they face more pressure to join the work force.

In an effort to turn things around, colleges are adding sports teams and majors in fields that tend to attract more men than women, such as criminal justice and information science. They are creating mentoring and advising programs for men, particularly those who are Black and Hispanic. And at least one is hiring a director of Black and males of color‘s success.

But programs and positions catering to men remain relatively rare, said Adrian H. Huerta, an assistant professor of education at the University of Southern California who studies programs for men of color. Those that do exist tend to be untested and underfunded — “a person who is dedicating 25 percent of their time and asked to produce miracles with no money,” he said.

James Shelley, who founded one of the nation’s first men’s resource centers at Lakeland Community College, in 1996 — “the prehistoric period,” he calls it — said many college leaders still view men as a privileged class.

“One thing I often hear is that men still have most of the power, they still make more on the dollar than women, so why create a special program for them?” he said. “It’s not an easy sell.”

Young women have outpaced young men in college enrollment since the late 1980s but the gap in favor of Black and Hispanic women goes back even further.

In 1972, when white women between the ages of 18 and 24 trailed their male counterparts by 10 percentage points in college enrollment, Black and Hispanic women were only 5 and 3 percentage points behind their male counterparts, respectively.

By 1980, Black and Hispanic women had caught up and surpassed their male peers. White women wouldn’t overtake men for another decade.

Thomas A. DiPrete, a professor of sociology at Columbia University and co-author of The Rise of Women: The Growing Gender Gap in Education and What It Means for American Schools, attributes this disparity to a history of labor-market discrimination.

Up until the 1960s, many of the jobs that required a college degree were essentially closed to white women and people of color, in general. Women of all races still went to college to become nurses and teachers, but “Black men didn’t have the same incentives to get college degrees that white men had,” DiPrete said.

We are losing a generation of men to Covid. We need to be really creative about how we get them back in the pipeline.

This pattern persisted even as the labor market began to open up more opportunities for women, prompting more women of all races to enroll. In 2018, the female-male gap in enrollment among 18- to 24-year-olds stood at eight percentage points for Black and Hispanic students, andsix percentage points for white students. Over all, nearly three million fewer men than women enrolled in college that year.

Some of this difference may be due to the belief among some young men that college “isn’t worth it” — that they’re better off going into the work force and avoiding the debt.

“In a lot of communities of color, there’s this mind-set that the man should work, the man should provide,” said Michael Rodriguez, director of the Men’s Resource Center at Kingsborough Community College, in Brooklyn, which is part of the City University of New York. “They think, ‘if I sit around and go to school, I may not be looked at as a functioning provider in my home.’”

Though the decision to work after high school may make short-term economic sense, it deprives these men of thousands in lifetime earnings, and deprives colleges of the perspectives they would bring to the classroom — both as students and as future professors, Rodriguez said. “For colleges to really thrive, all voices need to be heard,” he said. “A gender gap creates unhealthy institutions.”

Until relatively recently, men who skipped college could count on a family-sustaining wage in a male-dominated, blue-collar field like manufacturing. But those types of jobs have become scarcer, while the earnings gap between men with high-school diplomas and college degrees has grown wider. Today, men with bachelor’s degrees make roughly $900,000 more in median lifetime earnings than high-school graduates who lack higher degrees, according to the Social Security Administration.

Though well-paying jobs are still available for men without a four-year degree — jobs in the skilled trades, and advanced manufacturing, for example — most require at least a certificate or associate degree.

“I don’t know if there has been a full coming to grips with the way the economy has changed,” said DiPrete. “We’re still close enough to this world that, in some senses, has gone past, a world where a man could support his family without a college degree, working in a factory.”

But labor-market factors alone can’t fully explain the growing gulf in college completion between men and women. Academic preparation and gender norms play a role, too.

The differences between boys and girls emerge as early as elementary school, where boys lag in literacy skills and are over-represented in special education. Boys are also more likely than girls to be punished for misbehaving — an experience that can sour them on school.

The disparities in discipline are the most pronounced among Black boys, who made up 15 percent of public-school students in the 2015-16 school year, but accounted for 31 percent of law-enforcement referrals and arrests.

Boys are also less likely than girls to seek or accept help for their academic and emotional struggles, having been socialized to be self-reliant. By the time they’re in middle school, some boys have disengaged from school entirely. Even if they manage to graduate from high school, these boys lack the skill — or the will — to succeed in college.

Meanwhile, parents and schools “are pointing fingers at one other,” trying to place the blame for the gender divide, Huerta said.

“Is it the institution’s fault, or the family’s fault?” he asked.”

It is likely both!

Tony